A Gender-Imbalanced Judiciary

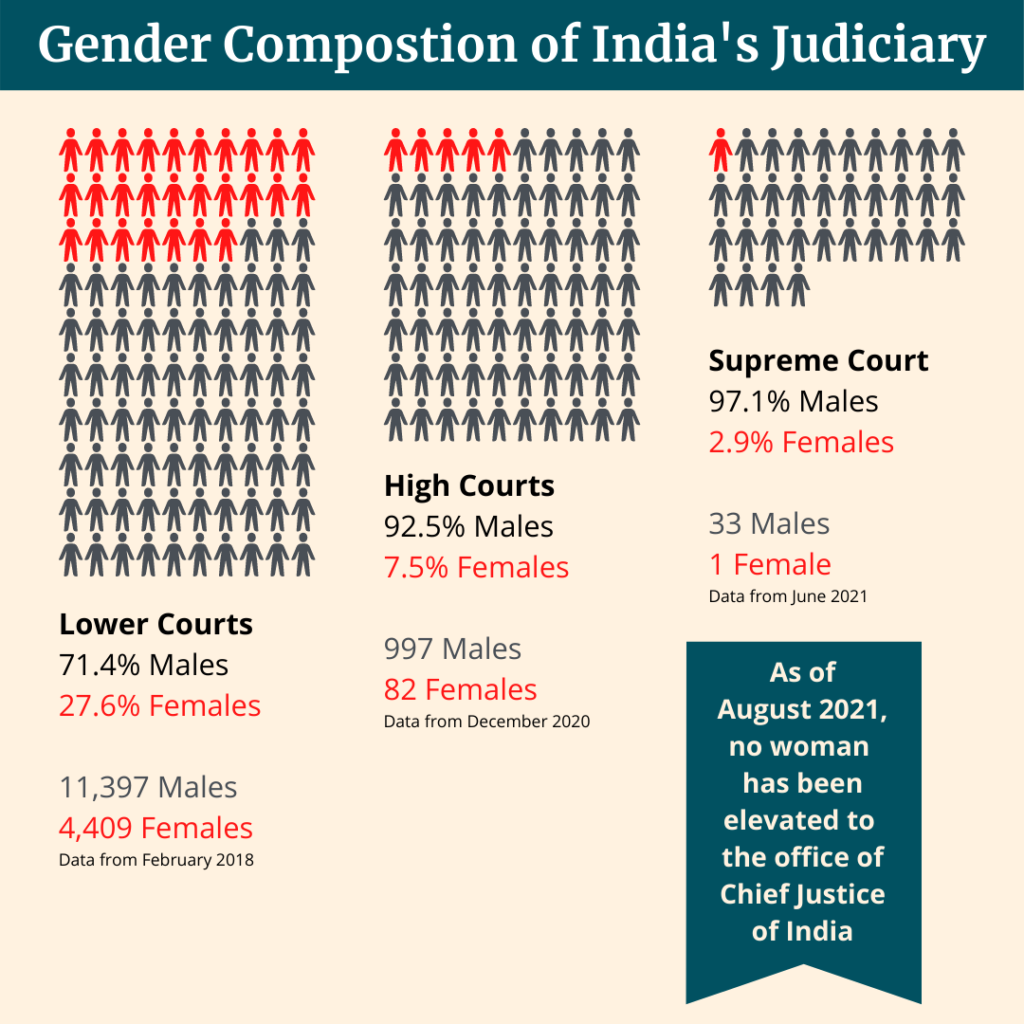

As of February 2018, the total number of judges in India’s lower judiciary was approximately 15,959. Out of these judges, about 11,397 (71.4%) were men and 4,409 (27.6%) were women. Figures from two and a half years later show that the strength of judges across High Courts in India was 1,079. Of these 1,079 judges, only 82 (7%) of them were women. From independence till the year 2019, there have been a total of 622 Chief Justices of High Courts in India and only 17 (less than 3%) of them have been women. As of 2021, no woman has ever been a Chief Justice of India at the Supreme Court.

The gender composition of the Indian Judiciary is male-dominated. It shows that there are a wide variety of factors that play a role in judicial appointments in India. What are these reasons and why do they matter? Let’s explore the life story of Justice Hima Kohli and try to answer this question. This is because Hima Kohli is someone who overcame the challenges faced by women in the Indian judiciary. So much so that she achieved something even what most male judges could not – an elevation to the position of Chief Justice of a High Court.

In January 2021, Hima Kohli became the first female Chief Justice of the Telangana High Court. Her story can serve as an inspiration for women who aim to achieve great things when the odds are not in their favour. But before we dive further into her story, let us try to understand why increased participation of women in judicial systems is a pressing need for society. What does Hima Kohli’s success as a woman in contemporary India symbolise? Why do we need more female judges at the altars of justice in our republic?

The entry of women judges into spaces from which they had historically been excluded has been a positive step in the direction of judiciaries being perceived as being more transparent, inclusive, and representative of the people whose lives they affect. By their mere presence, women judges enhance the legitimacy of courts, sending a powerful signal that they are open and accessible to those who seek recourse to justice.

Judge Vanessa Ruiz, President of the International Association of Women Judges. Source

Discrimination against women is deeply ingrained in our system for a variety of complex reasons with historical and socio-economic roots. There is no doubt that India as a country has made great strides and progress in almost every aspect, including gender empowerment. However, we still have a long way to go as a society. According to the data released by National Statistical Office (NSO) for 2017-18, the female literacy rate lags behind the male literacy rate by 14.4%. Further, there is discrimination against women at workplaces who receive lower salaries than their male counterparts. The 2018 Monster Salary Index (MSI) had revealed that the median gross hourly salary for men in India(₹242.49) was ₹46.19 more than women (₹196.3).

Crime against women is still a rampant issue. In 2019, there was a 7% increase in crime against women with an average of 87 rape cases per day being reported across India. Even though rape and sexual assaults are the crimes that get highlighted in the news, the crime that holds a larger number of cases and still goes unnoticed is domestic violence. It can be argued that a higher number of female judges will curb the ‘boys will be boys’ attitude that is so pervasive in India while interpreting the law and adjudicating on matters where women are victims.

The lack of women in the judiciary can itself act as a deterrent for other women who wish to serve their country and society. Subtle discrimination on the basis of caste, religion and gender has always existed and today we find ourselves in a male-dominated judiciary. Imagine if you were a female law school graduate who wanted to become a judge in India. Would you choose a career with a lack of gender parity and lifelong discrimination? On the other hand, a balanced system would allow for a diverse range of judges trying cases and providing different perspectives.

What does the Judiciary think?

Chief Justices of High courts have stated that many women advocates, when invited to come as judges, declined the offer citing domestic responsibilities about children studying in Class twelfth, etc.

– Justice Sharad Arvind Bobde, Former Chief Justice of India

Unfortunately, Justice Bobde’s remark fails to dig into the reasons why this is a problem. The reason is the transferability of the judge’s location. If women were supported at home like men are then their primary responsibility could shift towards their careers rather than being restricted to their homes. To achieve this organically, there must be a shift in our social behaviour. And such shifts in cultural paradigms are often a by-product of socio-economic progress.

‘According to a Civil Judge at a lower court in Uttar Pradesh, women are not able to become part of certain “circles”. The circles that are often filled with people who enjoy influence and power or are simply male-dominated.’

Source

As of May 2021, the lower judiciary has a total of 27% female judges. The high courts have only 7% and the Supreme Court is not even at 3 %. The situation worsens as one reaches the tip of the judicial pyramid. Evidently, the composition is better in the lower judiciary where the appointment is done through examinations with a candidate’s skill and knowledge taken into consideration. On the other hand, the upper judiciary for which the decisions of elevations are made behind closed doors remains skewed against women.

In 1994, Justice Sujata V. Manohar was elevated as a female Supreme Court judge. She retired in 1999 following which Justice Ruma Pal was elevated to replace her as the only female Supreme Court judge. A similar story unravelled around Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai’s retirement. When she was about to retire in 2014 from the Supreme Court, Justice R. Banumathi was elevated. This trend is also seen in the elevations of female Chief Justices of High Courts. In 2018, Justice Indira Banerjee, the only active female HC Chief Justice (at the Madras High Court) at the time was elevated as a Supreme Court judge. Subsequently, Justice Gita Mittal was appointed as the Chief Justice of Jammu & Kashmir High Court. Similarly, when Justice Gita Mittal was due to retire in December 2020, Justice Hima Kohli was elevated to the position of Chief Justice of Telangana High Court.

This can be coincidental. However, one might ask whether, at any point in time, the collegium attempts to keep at least one female High Court Chief Justice in the system as lip service. If true, there is a slight possibility that one of the factors that led to Justice Hima Kohli’s elevation was the need to conform to this undocumented practice. Nevertheless, this alleged and surprising practice alone cannot fully explain Justice Hima Kohli’s elevation. Hima Kohli is undoubtedly an aptly qualified professional with distinct experience and characteristics.

Hima Kohli – Journey to becoming a Judge

Let’s start with the dissimilarity from the instance of women declining the Judgeship. The quality and extent of Hima Kohli’s professional perseverance ensure that even if Hima Kohli was married, ridden with household chores and obligations, she would not have turned down the Judgeship. Fortunately for her, she has been unencumbered by such responsibilities. Be it a personal choice or exceptional professional determination – she decided against getting married and dedicated most of her life to the legal profession. To their credit, her parents and her sister have been very supportive and cooperative, giving her the incentive to work harder.

Born and brought up in Delhi in the 1960s, Hima Kohli was raised in a society recovering from post-colonial economic perils. The era of the Five-Year plans was in full swing. Her elder sister, Neelu, underwent protective parenting since she was the firstborn in their family. Hima Kohli, however, was placed under no such restrictions. Unlike her sister, Hima Kohli was made to travel via the school bus instead of the family car. She was even allowed to seek admission in a coed institution. Instead of going to a girls-only college like her sister, she went to St. Stephen’s College at the University of Delhi. Little did anyone know that the girl to do the small ‘first(s)’ in her family would go on to become a Chief Justice of a High Court.

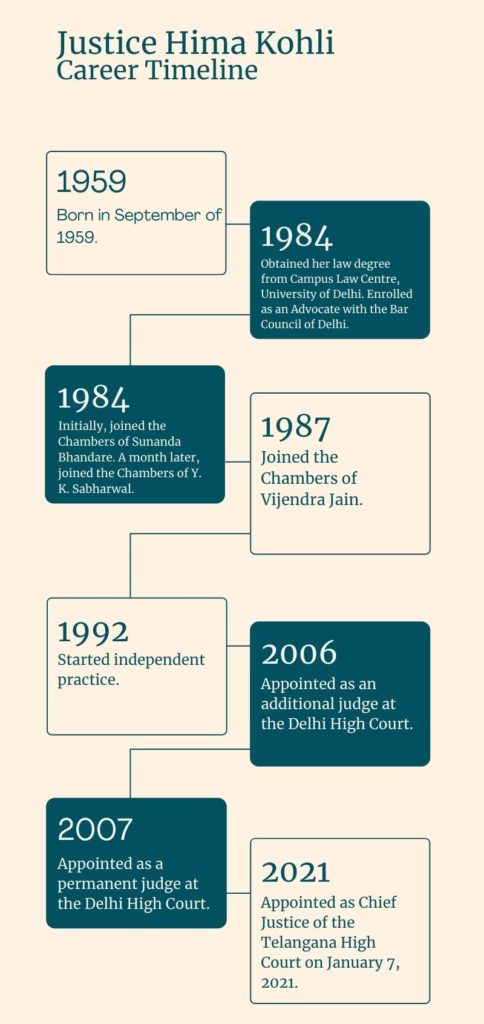

History was the subject of choice for her academically-oriented maternal family. Her great grandfather, her grandfather and his siblings were postgraduates and professors of History. Following in their footsteps, she pursued B.A. History at St. Stephens along with a masters degree in the same subject. She decided to give a shot at UPSC since her father had a disposition in favour of entering public service. Interestingly, the only reason she chose to do L.L.B was to obtain a library card which she thought would come in handy while studying for the competitive exam. (Read more about her school and college life here from pages 3-7). She soon realised that being a lawyer was her calling.

As a Lawyer

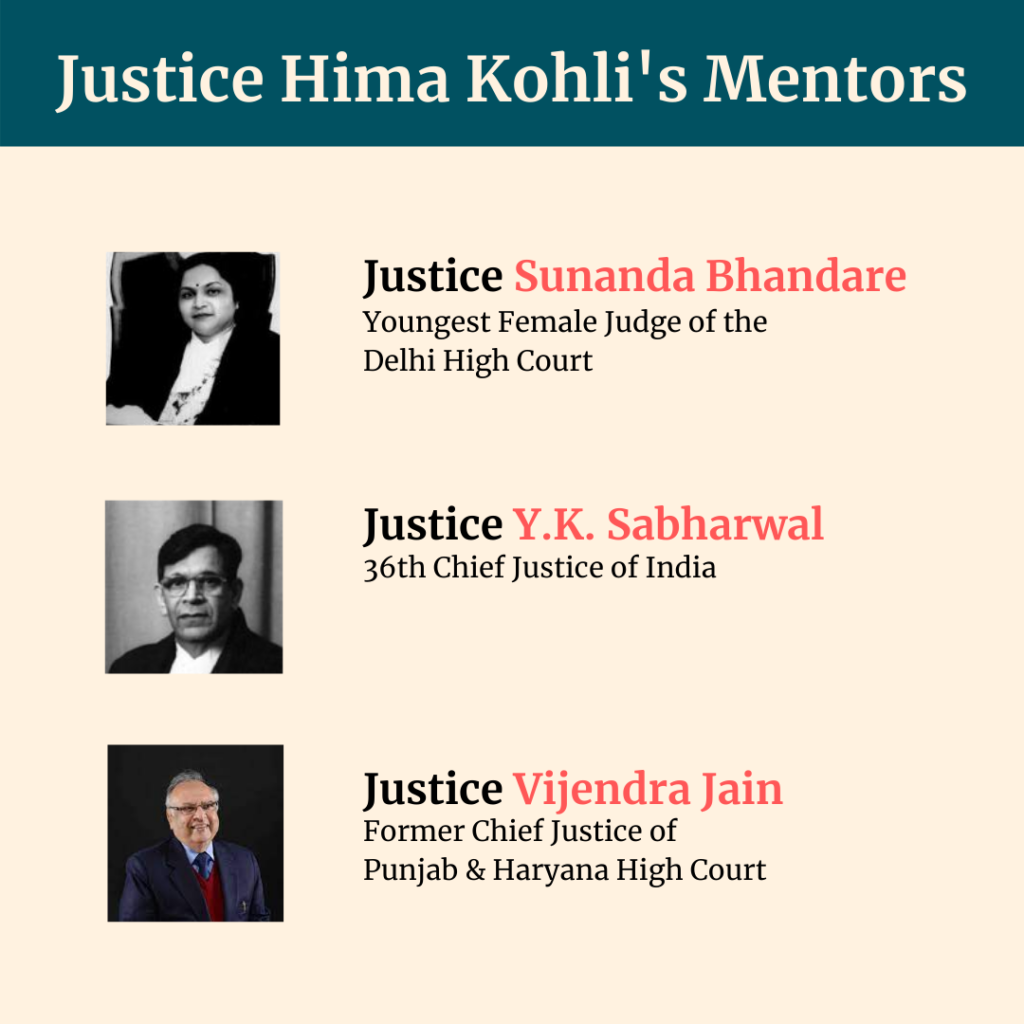

Hima Kohli was enrolled with the Bar Council of Delhi in 1984. She started her career in the same year by joining the chambers of Mrs. Sunanda Bhandare. Within one month of her joining, Mrs. Bhandare became Justice Bhandare when she was elevated to the position of a Delhi High Court Judge. Mrs. Bhandare referred Hima Kohli to Mr. Y.K.Sabharwal. Following this, she started working with him.

Besides having a large private practice, Y.K. Sabharwal was also the Standing Counsel (Civil), Government of NCT of Delhi and a Central Government Standing Counsel. His diverse profile provided Kohli with much-needed exposure and experience in both private and public practice. Mr. Sabharwal was the President of the High Court Bar Association at the time. He dealt with many important personalities which provided Kohli with substantial networking opportunities. In 1987, just like Mrs. Bhandare, Mr. Sabharwal became a Delhi High Court judge. Consequently, she had to change offices again.

Kohli went on to work at the Chambers of Mr. Vijendra Jain till he himself was elevated as a Delhi High Court judge in 1992. She then decided to continue her practice independently. Interestingly, all the three lawyers Hima Kohli worked with became High Court judges while she was working with them. They also achieved several notable milestones in the course of their careers.

This exemplifies the competency of Hima Kohli’s mentors as legal professionals. Whether it was Hima Kohli’s smart eye or sheer luck, such a career kickoff is truly rare!

There was no particular time when Hima Kohli realised she wanted to become a judge instead of a lawyer. However, her determination unconsciously aligned with it. In 2006, she was elevated as a Judge of the Delhi High Court. Fifteen years later, the Court bid adieu to Hima Kohli as she was honoured with the position of Chief Justice of High Court of Telangana.

In her farewell speech, Hima Kohli gave a shout out to many eminent judges and advocates. At the dawn of her independent practice, her paths had crossed with Mrs. Usha Kumar, a lawyer in Delhi High Court, who assisted her with the process fee form. Mr. M.L. Verma, who was later adorned by the Bench, helped her figure a way around with report drafting. Hima Kohli befriended Justice Valmiki Mehta, Justice Sanjiv Khanna and Senior Advocate B.B. Gupta, with whom she had lunch for a few years. She shared a Bench and a great bonding with Justice Gambhir, Justice Sistani, Justice Muralidhar and Justice Sanghi, who were elevated to the position of Delhi High Court judges on the same day as Justice Hima Kohli.

It’s all about who you know

During her practice, she worked with Dr. Justice M.K Sharma before he became the Chief Justice of Delhi High Court. He guided her through her first few judgements. Further in her farewell speech, Hima Kohli mentioned how Honourable Chief Justice of India, Justice Patel had always encouraged her and expressed her gratitude towards her innumerable colleagues: Justice Vipin Sanghi, Justice Siddharth Mridul, Justice Manmohan, Justice Endlaw, Justice Midha, Justice Shakder, Justice Mukta Gupta, Justice Kait, Justice Bakhru, Justice Sanjeev Sachdeva, Justice V.K. Rao… the list is endless.

It is seen that wherever she went and whoever she made contact with, she befriended them and/or learnt from them. Interestingly, these connections were not forced. In fact, they usually started from something as simple as a tea during breaks. With time, they developed into close personal relationships. Her naturally outgoing and social personality has assisted her in two ways in her career. Firstly, it not only helped her make friends but also learn something valuable from each encounter. Secondly, it helped her in expanding her network. This highlights her becoming a prominent law practitioner.

She has achieved countless milestones and has held several honourable positions such as the Standing Counsel for the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), Additional Standing Counsel for Government of NCT, Legal Advisor to Public Grievance Commission and National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India and Chairperson of Committee of the Delhi Judicial Academy and Delhi State Legal Services Authority Forum. She has multidimensional work experience and knowledge of diverse fields. Added to her seniority, this makes her a versatile judge.

A Judge is remembered by their Judgments

Hima Kohli typically deals with Writ Petitions challenging orders passed by the High Court on Administrative Side, Writ Petitions (Tender), Writ Petitions relating to MTNL, MCD & NDMC, Writ Petitions (AIIFR, BIFR, DRT, DRAT & Lokayukta), Writ Petitions (Co-operative Societies), First Appeals from Orders (Original Side), matters relating to street vendors/Tehbazari, Appeals against the orders of the Family Courts, Letters Patent Appeals up to the year 2017, matters to be heard by Commercial Appellate Division and regular hearing matters pertaining to these categories. As a judge, she holds an objective outlook and instructs individuals to uphold the law even in face of adversity. This, however, makes her demeanour strict and scrupulous.

She is known for her outstanding quality of judgments. She is responsible for giving the judgement – maternity leave cannot be a ground of dismissal (Manisha Priyadarshini v Aurobindo College, LPA 595/2019 & C.M.Applns.49913-14/2019, Delhi High Court). This decision was necessary and long overdue. It is one of the differentiating elements between male and female employees. In male-dominated workplaces, it becomes pertinent to remove this leave as a motivation for firing female workers.

This is not the only logical and progressive judgement given by her. She gave another sensible judgement in Rajat Gupta v Rupali Gupta (CONT.CAS(C)-772/2013, Delhi High Court) where it was held that mutual consent for divorce can be withdrawn before the final motion of the same under Section 13(B)(2) of the Hindu Marriage Act 1955. In Mukesh Yadav v Union of India and Ors. (W.P.(C) No.6062/2017, Delhi High Court), she contended that a juvenile’s identity need not be disclosed at any step of legal proceedings.

She has not shown any political affiliations publicly. This is why she comes across as being politically unbiased. There was an instance wherein the bench consisting of her and Justice Subramanium Prasad rapped the AAP government for not sanctioning basic funds for district courts. They also criticised the AAP government with regards to COVID-19 precautions, especially on weekend restrictions, night curfews, and wedding guest limits. However, this does not rule out affiliation as much as it highlights the legal conformity of Hima Kohli.

She was part of the bench that decided that adultery can only be committed after marriage. They also decided that allegations of having relations before marriage does not amount to adultery. Moreover, the bench contended that the new bride’s conduct of being in her room, unwillingness to perform household chores, or making a physical relationship is not cruelty to a husband (Vishal Singh v Priya & Pihu, MAT.APP.(F.C.) 327/2019 & C.M. No.53990/2019, Delhi High Court). As seen above, Hima Kohli’s judgements are mostly centrist. They liberate as well as control, stirring the society forward gently in an ever-changing culture. The strong quality of standing by logic over conventionality and emotion makes many of her judgements stand out.

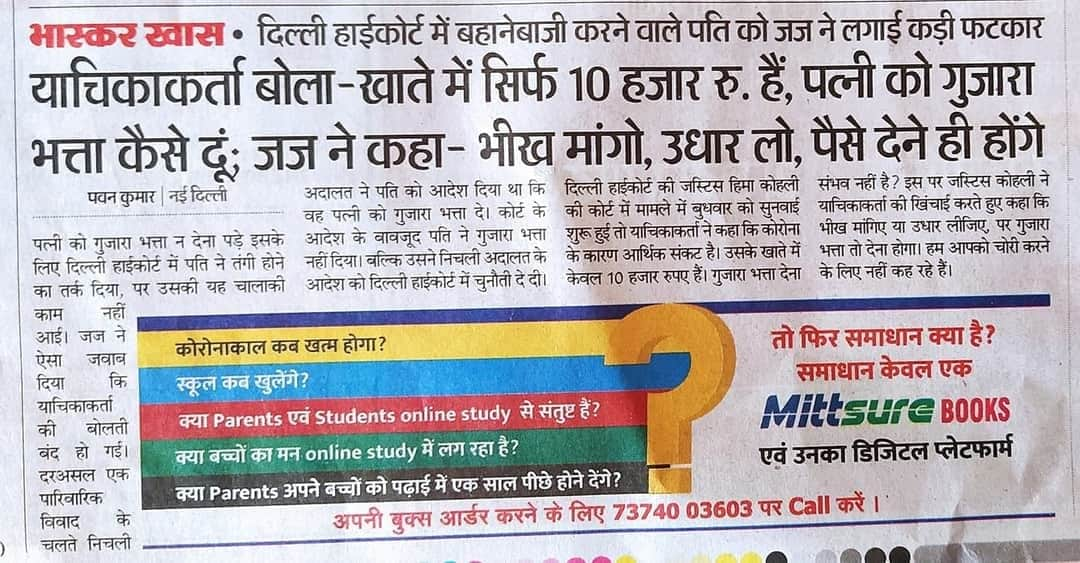

Ditching the legal jargon for once, let’s work out Hima Kohli’s temperament and nature through a layman’s perception of her judgements. Her decisions regarding flexibility in divorce procedures highlight her touch with reality. Aligning with the uncertain human nature, this shows the practicality of her viewpoints. She is known to advocate for women’s rights and empowerment even beyond the court mainly through online webinars, lectures and through other means. However, she has sometimes allegedly taken feminism far enough to border misandry. For instance, it was reported by Dainik Bhaskar that during a case hearing, the appellant pleaded that his financial status was bad owing to the pandemic and he couldn’t pay maintenance to his wife. Being indifferent to his plight, Justice Hima Kohli told him to borrow or beg for the money but pay the maintenance. Hima Kohli’s attempts to help women in the male-dominated world, sometimes, might go too far. Ironically, it is the feminist in her that brings out the misandrist in her.

As an Activist

Hima Kohli seems to be a progressive, practical, and partially feminist. Her perspectives and personality are reflected not only in her judgements but also in her lectures and advocacy for social causes.

Her ideas are eloquently reflected in the inspiring talks delivered by her. In a Webinar on ‘Domestic Violence During Lockdown: An Invisible Pandemic’, conducted by The Association of ILI Alumni and the Indian Law Institute, she claimed that no gender-neutral laws were required to address domestic violence issues. This contention also received social media backlash. In fact, this led to her being tagged as a ‘FemiNazi‘ by SheThePeople. Nevertheless, her thoughts were grounded in the practicality and the statistics of the affair.

Hima Kohli highlighted the key challenges presented before family courts in the Fourth Regional Conference on Sensitisation of Family Court Matters organised by Madras High Court and Tamil Nadu Judiciary Academy. She addressed the challenges faced by ‘Women of Indian Judiciary‘ in a speech at the Society of Women Lawyers, India. In a Youtube lecture on POSH Act, she highlighted the hypocritical workplace treatment of women in contrast with their valued positions in households.

She promotes environmental awareness and highlights the judiciary’s role in ecological preservation. She actively highlights the role of family courts in resolving family disputes. While working towards the improvement of the ecological and civil angle of the legalities, she actively promotes mediation as a substitute for dispute resolution. Moreover, she advises counsels to attend court to argue cases instead of seeking adjournments. Indeed, apart from being knowledgeable, she is eclectic in pursuance of legal development.

“However good a woman lawyer may be at her work, she has to work doubly hard to make a mark.”

From Hima Kohli’s farewell speech

What does it take to be a woman High Court Chief Justice in India?

For Hima Kohli, it was her utmost dedication, seniority, experience, diverse network, a wide range of interests, educative public appearances, and most importantly; her foreknowledge of knowing when to be progressive and when to be conventional in terms of judgements, along with a modicum of luck that helped her accomplish a feat many women aspire to achieve.

On March 13th 2021, Justice Indu Malhotra, one of the two female judges in the Apex Court, retired. Following this, the collegium is considering a female Supreme Court judge. It plans to elevate another female judge to fill the vacancy. Justice Hima Kohli’s name, along with Justice B.V. Nagarathna’s and Justice Bela M. Trivedi’s, is being discussed for Elevation. If elevated, her tenure, otherwise ending in September 2021, will be extended to 2024. Hima Kohli’s elevation to the Apex Court is a question that will answer itself shortly. However, the futuristic demographic structure of the Indian Judiciary remains a subject of debate.

There is an inherent bias in appointments and elevations. It seems to place a person’s caste and gender over merits. Since independence, there has only been one Chief Justice of India from the Dalit Community and one from the Sikh community. The decisions of the Supreme Court percolate down to the lives of all majorities and minorities alike. However, they are not able to partake in the Indian Judiciary. Similarly, women, who constitute almost half (48.5%) of the Indian population, have redundant representation in courts. In fact, according to Justice Sridevan, the Indian Judiciary is like an “old boys club“, which calls for immediate change.

Comparing with other Jurisdictions

A male-dominated judiciary is an obstacle that is not only limited to India. The United States Judiciary comprises 27% female and 73% male judges. India’s neighbouring countries like Nepal and Pakistan have poor gender compositions as well. In Nepal, only 12% of lawyers are female and the same disparity is reflected in the judiciary. Similarly, there are only 6 female judges in Pakistan’s High Courts out of a total of 113 judges. Furthermore, only 6 of the 198 members of the 7 bar councils in the country are women. Unfortunately, this disparity is a rather universal problem and is found in most countries. In fact, even the International Court of Justice has 3 female judges as opposed to 15 male judges.

In India, the collegium system is responsible for deciding the appointment and elevation of judges. The need of the hour is, thus, to reform the system if one hopes for any substantial improvements. A shift in the collegium’s tendencies cannot be forced but has to be organic. The average age group of the collegium members is 60-65. People who fall in this age group now were born and brought up in conservative societies. They are bound to practice some discrimination, even if it is unconscious. Only time will tell which way future collegiums will swing.

Research By: Shreya Chawla, Natasha Matange, Arya Gaddam

Edited By: Ahsnat Mokarim, Eklavya Dahiya