Becoming a High Court Judge in India

The dream of becoming a High Court judge in India is a challenging one. As of July 2021, there are a total of 1079 Judges across 25 High Courts in India of which 815 are permanent judges while the remaining are additional judges. The difference between permanent and additional judges is that the latter gets appointed for a term of two years, while permanent judges continue serving till their retirement age of 62. Judges may serve till the age of 65 if they are elevated to the Supreme Court. Additional judges can, of course, be promoted to a permanent judgeship based on need, and subject to the internal politics of India’s upper judiciary. Whether a judicial appointment is permanent or not, the position requires education, years of practice, intellect and a plethora of other factors to come together in your favour.

High court Judges are constitutional authorities. In simpler terms, this means that the Constitution of India talks about the establishment of High Courts as well as the posts of High Court judges. Article 216 of the Constitution establishes the office of the Chief Justice and Judges of the High Courts while Article 217 lays down the term, appointment and resignation procedures of the judges. Article 226 and 227 lay down the powers of High Courts to issue writs, and to be the ‘superintendent’ of all courts in the state(s) which fall under the purview of that particular High Court. The constitution goes on to elaborate more powers and procedures for High Courts. The detailed procedures for the functioning of courts are not provided in the Constitution. Instead, the state, as defined under Article 12 of the Constitution, uses the power of delegation to let the functionaries of state machinery establish procedure. To read more about these provisions you can refer to the text of the Constitution of India, with amendments (as of July 2021).

The power that comes with having judicial authority backed by the Constitution is immense. Each candidate is vetted through processes and mechanisms that are designed to eliminate all but the most deserving. At least that’s what the general notion is. But as we take a deep dive and look at the journey of one particular judge, one begins to see how wrong this most basic assumption can be, at least in some cases.

Ravi Shankar Jha – A Man With Powerful Connections

Family Background

Justice Ravi Shankar Jha is the son of late Shri Arun Shanker Jha. While not much is known about his father, Justice Jha’s grandfather Dr V.S. Jha is a Padma Bhushan awardee and ex-Vice Chancellor of B.H.U. Dr. Jha was the vice-chancellor of the Banaras Hindu University from 1956 till 1960. The list of notable alumni that have been a part of the BHU Faculty or have graduated from there is quite extensive, including a former President of India. Justice Ravi Shankar Jha’s great-grandfather was Rai Saheb Pandit Lajja Shanker Jha, founder of Pt. Lajja Shankar Jha Model School of Excellence in Jabalpur which was most likely one of the oldest schools in Madhya Pradesh. The school itself has produced many notable alumni as well including Dr. Sudhir Mishra who worked directly under President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam on the BrahMos project. Justice Abhay Manohar Sapre, who retired as a Supreme Court Judge in 2019 was also an alumnus of this school.

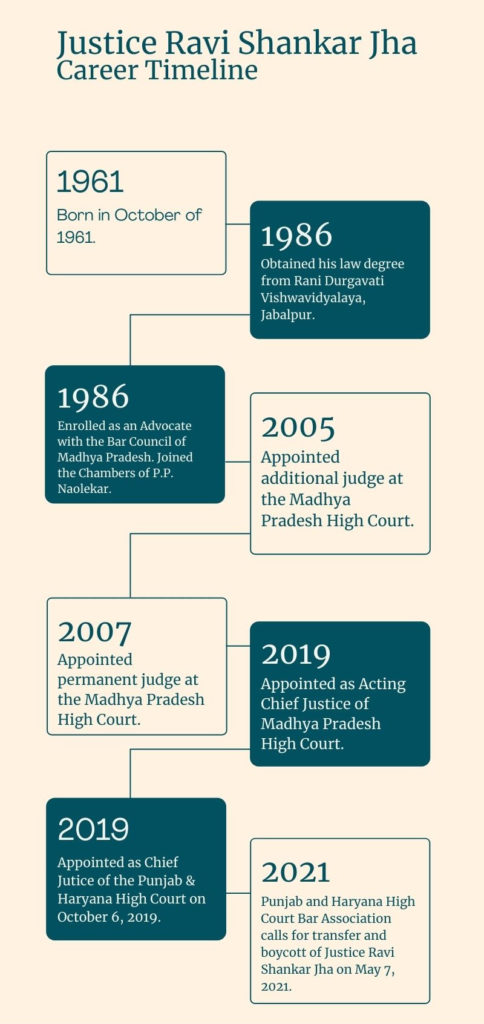

Suffice to say, Ravi Shankar Jha was brought up in a family of successful men and growing up around a crowd with power and recognition, it was only natural for him to desire the same. Justice Jha obtained a degree in law in 1986, from the Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalaya, formerly known as Jabalpur University. The prestigious university too holds a strong alumni network, ranging from ministers like Prahlad Singh Patel, the former Minister of Tourism and Minister of State for the Ministry of Jal Shakti as of July 2021, to former Supreme Court judges like Abhay Manohar, to professors like Acharya Rajneesh who is more popularly known as Osho. A controversial figure with a fiery story.

Camaraderie with a former Chief Justice of India

In October 2020, it was reported that the then Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde went to visit Kanha National Park and his hometown Nagpur in a special helicopter ride which was issued by the Madhya Pradesh Government. Lawyer and activist Prashant Bhushan had tweeted that such hospitable treatment was availed by the Chief Justice of India when an important case of disqualification of defecting MLAs of Madhya Pradesh was pending before him. The case was critical enough to determine the stability of the Madhya Pradesh government.

It was further reported that Justice Ravi Shankar Jha (the Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court) along with Justice Ajit Singh (Odisha Lokayukta) and Purushaindra Kaurav (the advocate general of Madhya Pradesh) were also seen accompanying Justice Bobde in this chopper ride from Jabalpur to Kanha. They also stayed with him throughout for two nights and three days. Justice S.A. Bobde’s time as the Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court also overlapped with that of Justice Ravi Shankar Jha’s tenure at the Madhya Pradesh High Court which is probably where the two got so well acquainted.

According to the Wire, this meeting happened at the same time when the Supreme Court Collegium was considering the elevation of Justice Jha to the Supreme Court and the appointment of Kaurav as a judge in the Madhya Pradesh High Court. Justice Ajit Singh was reported to be lobbying for the appointment of Odisha Chief justice Mohammad Rafiq as the Chief justice of the Madhya Pradesh high court, which was then headed by the acting Chief Justice Sanjay Yadav.

As a Lawyer

On 20 September 1986, Ravi Shankar Jha was enrolled as an advocate with the Bar Council of Madhya Pradesh. During his practice years, he began working with P.P. Naolekar, one of his seniors from Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalaya. As of July 2021, Justice P.P. Naolekar is the Lokayukta (an anti-corruption authority constituted at the state level) of Madhya Pradesh. He was formerly a Judge of the Supreme Court of India, with landmark judgements like the petitions challenging section 377 of the IPC under his name. Section 377 of the IPC is a famous section that criminalises, amongst other things, homosexuality. Read more about Justice P.P. Naolekar’s role in this case.

Ravi Shankar Jha practiced at the Central and State Administrative Tribunals after their establishment in 1985. He also handled cases related to civil services, election, taxation, criminal and constitutional matters for the state of Madhya Pradesh. He has been the counsel for various government-owned enterprises such as Bhilai Steel Plant, Food Corporation of India, M.P. State Minor Forest Produce Trading & Development Federation, among others. After 19 years of legal practice at the Madhya Pradesh High Court he was elevated as an Additional Judge in 2005. In 2007, his elevation was solidified when he became a Permanent Judge at the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

Controversial Elevation as the Acting Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh

On 10th May 2019, amidst the 17th Lok Sabha elections, the Collegium comprising the then Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi along with Justices S.A. Bobde, N.V. Ramana, Arun Mishra and R.F. Nariman had recommended the appointment of Justice Akil Kureshi as the Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court. The recommendation was made in the backdrop of Chief Justice Sanjay Kumar Seth’s retirement in the following month on 9th June 2019. Along with Kureshi, three other names were recommended by the Collegium for elevation as the Chief Justices to different High Courts. These included Justice V. Ramasubramanian to the Himachal Pradesh High Court, R.S. Chauhan to Telangana High Court and D.N. Patel to Delhi High Court. Subsequently, the names of the rest were cleared in the month of June by the centre and each of them was elevated to their respective High Courts. However, this was not the case at Madhya Pradesh High Court.

The central government, on 7th June 2019, released a notification appointing Justice Ravi Shankar Jha, the senior-most puisne judge of the Madhya Pradesh High Court as its Acting Chief Justice with effect from 10th June 2019. This notification was issued at the time when the recommendation of Justice Akil Kureshi by the Collegium was still pending. The reason behind the centre’s decision to overlook Akil Kureshi is allegedly linked to a few of his judgements at Gujarat High Court that went against the interests of the current Home and Prime Ministers, Amit Shah and Narendra Modi. Keeping the politics aside, the reasons behind the centre’s decision to sit on the Collegium’s recommendations and then appoint another judge for the same vacancy without clarification further fuels this mystery.

Read the full story of Akil Kureshi’s conflicts with the central government.

Article 223 of the Indian Constitution deals with the provision of appointment of Acting Chief Justice. Under this Article, the President can appoint any other judge from the said High Court to perform the duties of the office of Chief Justice during a situation of vacancy due to retirement or any other reason. The current Memorandum of Procedure dealing with the appointment and transfer of Chief Justices and Judges of High Courts prescribes that when the seniormost puisne Judge on duty is proposed to be appointed as the Acting Chief Justice, the central government should inform the Chief Minister and issue the notification of appointment in the Gazette of India (Para 9 of the MoP). The appointment of Ravi Shankar Jha by the centre is said to have been made under these very provisions.

The government can conduct an inquiry, raise objections and can request a reconsideration of the recommendations of the Collegium. However, if the latter reiterates its recommendation, then the decision is binding on the government. Thus, in order to sideline this process, a trend of delaying appointments that the centre may not approve of has been noticed over the past few years.

The MoP also mandates that when there is a proposal to appoint an Acting Chief Justice other than the seniormost puisne Judge, the procedure for appointment of a regular Chief Justice will have to be followed. When the Chief Justice of India initiates the proposal to appoint a Chief Justice of a High Court, the process of appointment must be initiated well in time to ensure the completion at least one month prior to the date of anticipated vacancy for the Chief Justice of the High Court (Para 5 of the MoP). In this case, the appointment of Justice Ravi Shankar Jha raises an interesting question because the recommendation to elevate Justice Kureshi as the Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court was made on 10th May 2019, a month before the vacancy could actually arise in the Madhya Pradesh High Court. The vacancy only arose after the delay made by the centre to actually approve the recommendation. So all the government had to do was delay the appointment of Kureshi and Justice Ravi Shankar Jha would automatically be elevated as Acting CJ.

It is to be noted that after the landmark Three Judges Cases, the Collegium maintains primacy over judicial appointments. The government can conduct an inquiry, raise objections and can request a reconsideration of the recommendations of the Collegium. However, if the latter reiterates its recommendation, then the decision is binding on the government. Thus, in order to sideline this process, a trend of delaying appointments that the centre may not approve of has been noticed over the past few years. The above case serves as a prime example of this trend. While attempts to amend the MoP have been made following the Supreme Court’s decision to strike the National Judicial Appointments Commission as unconstitutional in 2015, no reported progress has been made due to the disagreements between the centre and the Supreme Court on various subjects.

Elevation to the Punjab and Haryana High Court

After serving for four months as the Acting Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court, Justice Ravi Shankar Jha was recommended by the Collegium for an elevation to the position of the Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court on 28th August 2019. A week later, on 6th October 2019, he was sworn in as the Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court.

Boycott from the Punjab and Haryana High Court Bar Association

The Chief Justice has not cooperated with the Bar and has also taken least interest in the problems faced by the general public of the states of Punjab, Haryana and Union Territory of Chandigarh. Despite various requests and offers of viable solutions, the Chief Justice has remained adamant and has done little for the growth of the institution, legal fraternity and general public of both states and the UT.

Source

Justice Ravi Shankar Jha was caught in a controversy when Punjab and Haryana High Court Bar Association (HCBA) passed a resolution calling for a boycott along with the transfer of the Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court in May 2021. The HCBA statement added, “The Chief Justice has not cooperated with the Bar and has also taken least interest in the problems faced by the general public of the states of Punjab, Haryana and Union Territory of Chandigarh. Despite various requests and offers of viable solutions, the Chief Justice has remained adamant and has done little for the growth of the institution, legal fraternity and general public of both states and the UT”. The association was upset about the non-resumption of physical hearing of cases since March 21, 2020, even though movie theatres, schools, schools, gyms, religious places, political gatherings and malls continued to function to their full capacity.

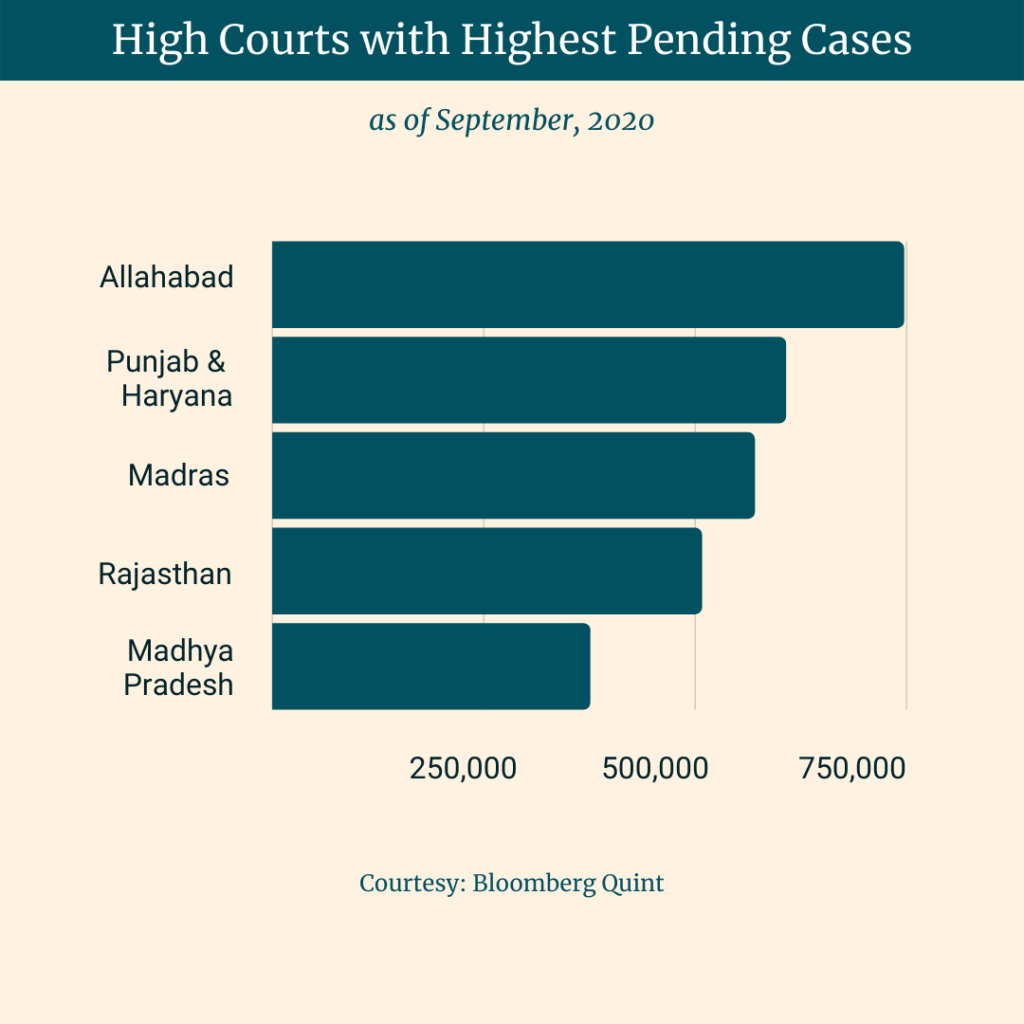

Furthermore, the HCBA executive committee expressed concerns over non-listing of critical matters, especially habeas corpus petitions, anticipatory bails, regular bails, suspension of sentence, stay matters and other matters involving a violation of fundamental rights. It contended that the mechanism of filing petitions/cases established during the coronavirus period had an arbitrary process of mentioning without which the citizens could not approach the high court. Even after modification, the procedure had various mentioning issues. According to the Bar, “More than 300 written complaints and numerous oral complaints have been received in the office of the executive committee regarding wrongful rejection of mentioning and use of pick and choose policy in allowing limited cases”. The statement also mentioned that the strength of the bench was reduced from 46 to 11 on the virtual mode which had further increased the backlog of cases in Punjab and Haryana High Court – the high court with the second-highest pending cases in the country.

In response, the Bar Council of Punjab and Haryana passed an order staying the resolution of the High Court Bar Association (HCBA) to boycott the Court of the Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court until his transfer to some other court. This order was also supported by the Bar Council of India which formed a seven-member committee to meet the Chief Justice and resolve the matter amicably. The BCI said, “The demand of transfer of the Chief Justice prima-facie does not seem to be proper and justified, nor is going to solve the problem. Such politics should not be allowed to be played in any Bar Association.” It also requested Chief Justice Ravi Shankar Jha to listen to the grievances of the lawyers and redress them as far as “practicable and feasible”.

Disciplinary Action Against Officers

The High Court of Punjab and Haryana created waves once again after it initiated proceedings against some of its judicial officers as reported by Tribune India. The orders gained attention as it was supposedly the first time that such large-scale action was taken against judicial officers – sending a strong message of “zero tolerance against indiscipline, complacency, and other factors in the subordinate judiciary”. Two Additional District and Sessions Judges VP Gupta & Rajinder Goel were forced to retire while Punjab-cadre officers Abhinav Sekhon and Nazmeen Singh were discharged during probation. In addition, Sub-Judges Tanvir Singh and Pradeep Singhal were suspended and investigations were initiated against Haryana-cadre judicial officer RK Sondhi and Punjab-cadre officer Tejwinder Singh – the judge who had convicted the accused rapists in the infamous Kathua case.

The Controversy involving Justice S. Muralidhar

The “Midnight” Transfer from Delhi to Punjab

While Justice Jha was transferred to the Punjab and Haryana Court, there were a large number of changes taking place in the political affairs of our country. After the 17th Lok Sabha elections (that took place in April – May 2019), the National Democratic Government pulled off a landslide victory with Mr. Narendra Modi returning for a second term as the Prime Minister of the country. The stronger political grasp of the NDA government brought out a series of landmark decisions that give the year 2019 a special place in history books. Examples of a few of these events in chronological order include; abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in August 2019 which led to the removal of the special status for the state of Jammu and Kashmir provided to it since 1954, the Supreme Court’s final verdict on the years-long-controversial issue of Ram Mandir and Babri-Masjid in November 2019, and lastly, the introduction of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 that was passed in December 2019.

Each of these events came with a new set of controversies that stirred political tensions throughout the country. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 received a lot of flak and support from different sections of society. As a result, protests, both supporting and opposing the said act, broke out in different states. The national capital, in particular, was the centre of these public demonstrations. However, in February 2020, things took a turn for the worse when violent riots started in northeast Delhi. Read more about the infamous Delhi riots here. As the Delhi High Court was still dealing with the crisis, one of its judges’ names garnered a lot of attention when his transfer was approved overnight by the central government and communicated personally by the Chief Justice of India at midnight. The judge’s name is Dr. S. Muralidhar, who was the third seniormost judge at the Delhi High Court at the time.

On 26th February 2020, Justice Muralidhar, while hearing several petitions associated with the riots had rebuked the Delhi police and the central government for not registering FIRs against the BJP leaders Anurag Thakur, Parvesh Verma and Kapil Mishra, among others who were accused of making hate speeches and inciting violence. He, along with Justice A.J. Bhambhani, held an emergency sitting around 12:30 a.m after a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed seeking safe passage of ambulances carrying the injured riot victims. This was done under the orders of Justice G.S. Sistani (the second seniormost judge at the Delhi High Court) since Chief Justice D.N. Patel was on official leave for the day. Interestingly, the very same day, the central government released a notification approving the transfer of Justice Muralidhar to the Punjab and Haryana High Court. The transfer recommendation was made by the Collegium only 14 days prior (12th February 2020) to the approval.

While there is no fixed period within which the centre has to approve or disapprove of a specific recommendation, the fact that any ruling government can delay or hurry with recommendations of judges in a manner that suits their interests highlights the loopholes in the procedure of judicial appointments.

In the present case, it was the timing and the hasty nature of the transfer that attracted a lot of criticism from the legal fraternity and the public in general. The Delhi High Court Bar Association (DHCBA) passed a resolution protesting the controversial transfer. The Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Reforms (CJAR) released a statement saying that the “rushed manner in which the transfer notification has been issued by the Centre cannot be ignored”. It further added that the entire purpose of the transfer was to “punish an honest and courageous judicial officer for simply carrying out his constitutional duties”. Dushyant Dave, the President of Supreme Court Bar Association, had also raised concerns at “the manner and haste” in which the transfer was done, calling it “absolutely malafide and punitive”.

While there is no fixed period within which the centre has to approve or disapprove of a specific recommendation, the fact that any ruling government can delay or hurry with recommendations of judges in a manner that suits their interests highlights the loopholes in the procedure of judicial appointments. It also raises questions on the independence of the judiciary from political influence.

Second or Seventh Bench?

Soon after Justice Muralidhar moved to the Punjab and Haryana High Court, another controversy arose with respect to the work that was handed down to him. Justice Muralidhar was the second most senior judge behind Chief Justice Ravi Shankar Jha. In accordance with the seniority index, Justice Muralidhar sat on the second bench, which was earlier headed by Justice Rajiv Sharma who was now presiding over the third bench. However, the second bench was relegated with matters that were earlier being heard by the seventh-bench which included judges who were much lower in seniority than Justice Muralidhar. According to the roster of division benches decided by the Chief Justice, the second bench was assigned all matters related to taxation, appeals under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) and Benami Property Transaction Act, petitions under PMLA, FERA and Foreign Trade Development and Regulation Act; writ petitions challenging the constitutional validity of any act, rules of notification related to tax including municipal laws.

On the contrary, the previous second bench, headed by Justice Rajiv Sharma, dealt with important matters of public interest. These included cases related to banking transactions, intelligence agencies (other than CBI) such as the R&AW, Aviation Research Centre and Intelligence Bureau, all service matters, all writ petitions other than those assigned to other division benches, civil references, criminal appeals, leave to appeal, appeals against acquittal. criminal writ paroles. All these matters were now assigned to the third bench instead. It has been reported that the lawyers at the high court considered this move as “an attempt to marginalise” the judge. Since the roster of division benches is finalised by the Chief Justice of that court, Justice Jha’s decision to assign lesser important cases to Justice Muralidhar has been subjected to criticism. Senior advocate Anupam Gupta has said, “The Chief justice has betrayed lack of judicial courage in limiting Justice Muralidhar’s bench to tax matters. It would be naive not to see the grim political reality behind this specific exercise of the Chief justice’s powers as Master of the Roster.”

It seems that politically important cases are to be kept away from Justice Muralidhar. The factors that led to his midnight transfer from Delhi when he was hearing the sensitive Delhi riots case seem to have weighed here as well. One hopes that this is only a transitory phase.

Source

What is important to note is that Justice Muralidhar has both seniority and experience on his side. He has delivered a plethora of landmark judgements and was partly responsible for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in India in the Naz Foundation case. He also convicted Congress leader and former MP Sajjan Kumar in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots case and held members of UP’s 16 Provincial Armed Constabulary personnel guilty in the 1986 Hashimpura killings of 42 people in Meerut. A fearless man, Justice Muralidhar has always chosen to do what is right, instead of what is right for him. Based on available sources, he has given more than a total of 20,000 judgements and orders as a judge. Moreover, his judgements have been cited by other judges more than 700 times in the past five years which is the highest when compared to other judges for the same time period.

The data presented above establishes that Justice Muralidhar was more than competent to handle important cases of public interest. This poses a number of questions as to why a judge of such calibre and seniority is relegated to dealing with matters of the seventh bench. Was Justice Muralidhar being punished for having gone against the interests of the ruling parties? Was the Chief justice under any pressure to enforce this punishment? Was the Chief justice ordered to marginalise Justice Muralidhar from matters of public importance or was he simply doing what he thought was best for the greater public good? While all the above questions are mere speculation, an affirmative answer to any of these questions would only mean a precarious threat to the independence or efficacy of the judiciary.

In May 2020, a division bench headed by Justices J.B. Pardiwala and Ilesh J. Vora of the Gujarat High Court had strongly criticised the state government over its handling of the covid crisis. The bench, after taking cognisance of media reports, was hearing suo motu cases on the high mortality rate in the Ahmedabad Civil Hospital and issues of the migrant labourers. However, a few days later, the bench was reshuffled which then included Chief Justice Vikram Nath as the presiding judge with Justice Pardiwala as the junior judge. The question has to be asked – are Roster Changes that suit the needs of the Executive becoming a trend?

As former Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde said, “Let justice be done though heavens may fall”, it is hard to leave justice to a judiciary that is not as independent as it claims to be. What is the significance of a judiciary if a judge has to think twice before giving orders that are subject to external considerations and vested interests? Fortunately for us, our country is still a democracy – however meek it might seem. Unfortunately for us, realising true change is going to take sacrifices that we do not wish to make. Like a frog in a boiling pot of water, we begin to do something when it’s already too late.

Research By: Kashish Siddiqui Khan, Aastha, Soumiki Ghosh, Dhruv Jain

Edited By: Eklavya Dahiya and Ahsnat Mokarim