In-house Inquiry Against Justice Mahanty

It is clear from a review of the material that the charges against him (Indrajit Mahanty) are very serious and backed with adequate documentary evidence. The allegations against Justice Mahanty relate to acts of grave judicial impropriety and conflict of interest, tantamount to a clear breach of judicial ethics.

CJAR Letter to Justice Vazifdar

In September 2016, a complaint was filed by RTI Activist Jayanta Kumar Das alleging abuse of power and authority by Justice Indrajit Mahanty and Justice Sangam Kumar Sahoo. Das cited various affairs to back his claim. Consequently, then Chief Justice of India, T.S. Thakur ordered an inquiry by an in-house committee into the conduct of the judges in question. This committee was headed by Justice S J Vazifdar, Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, and comprised Justice T Vaiphei, Chief Justice of the Tripura High Court, and Justice S Abdul Nazeer, then a judge of the Karnataka High Court. In February 2017, Justice Arun Tandon of Allahabad High Court replaced Justice Nazeer as the latter was elevated to the Supreme Court. Amidst the dragged-out investigation, a considerable amount of incriminatory information and evidence surfaced against Mahanty. The entire deal was somewhat dubious. Nonetheless, the probe did not culminate in any action nor was the committee’s report made public. Allegedly, the report was not even furnished to the complainant. It is surprising how an investigation against a senior judge on such grave allegations does not seem to have been followed thoroughly. In fact, Justice Mahanty is now (2021) the Chief Justice of the Rajasthan High Court. Justice Indrajit Mahanty’s story is indeed a story of mysterious twists and turns.

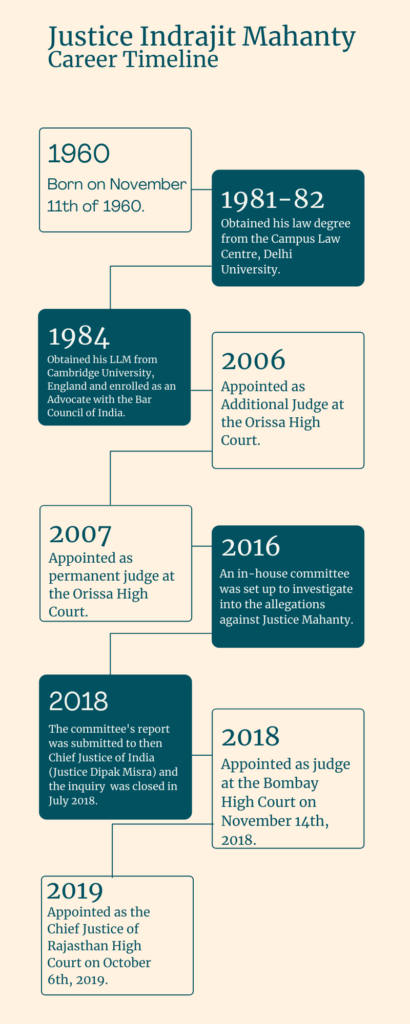

Journey till becoming a Orissa High Court judge

Indrajit Mahanty was born on November 11th, 1960, to advocate Smt. Shakuntala Mahanty and late Ranjit Mahanty, Barrister at Law. His brother, Biswajit Mahanty, went on to establish the Barrister Ranjit Mahanty Group of Institutions (BRM). While Indrajit Mahanty is not directly hands-on in the education business, his brother is the chairman of the BRM Trust and runs many private educational institutes such as BRM International Institute of Technology (BRM-IIT). Biswajit Mohanty is also a trade unionist and lobbyist, who heads Odisha Technical College Association (OTCA), which lobbies for filling up more seats in such colleges, along with Odisha Private Engineering College Association (OPECA). Indrajit Mahanty, on the other hand, pursued a career similar to his parents. Raised by individuals working in the legal field, Mahanty was keen to take on the profession himself. He studied at Mount Hermon School, Darjeeling following which he did B. Com. Honours from Ravenshaw College, Cuttack, Odisha. He obtained his L.L.B. from Campus Law Centre, University of Delhi. He also did L.L.M from University of Cambridge, England.

In 1984, Indrajit Mahanty enrolled as an advocate with the Orissa Bar Council. He began his legal practice under his father until his demise in the year of 1989. Following this, he began independent practice in the fields of Commercial Law, Arbitration, Taxation, Civil and Criminal, Writs and Service Law. He appeared before the Civil Courts, Orissa High Court as well as the Supreme Court. He also conducted a few arbitration proceedings in London. After 17 years of independent practice, on March 6th, 2006, Indrajit Mahanty was elevated to the position of judge in the Orissa High Court. Owing to his parents’ designations, Mahanty was well connected in the legal fraternity. One might wonder whether nepotism had a role to play in his elevation. Assuming that it did, chances of it being a dominant factor are minimal. His education background and career trajectory are testaments to the fact that Mahanty is a professional with experience, skills and knowledge.

Misfortunes of Ravenshaw University

Most of the defining points of Justice Indrajit Mahanty’s journey as a judge in the Orissa High Court, ironically, are happenings from outside the courtroom. The first set of affairs that hit the radar of critics were the cases involving Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, Odissa. In 2000, before the college was deemed a University (2005), it signed an MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) to start professional courses in ‘public private partnership’ with Star Computer Institute Pvt. Ltd. This institute belonged to Justice Indrajit Mahanty’s brother, Biswajit Mahanty. This MOU was renewed for another three years in 2011. Upon its expiration in 2014, the University refused to renew the MOU with Star. This was reasonable as UGC’s guidelines prohibited Ravenshaw from entering into such agreements: ‘No university whether central/state/private can offer its programme through franchise agreement even for the purpose of conducting courses through distant mode’. Nonetheless, this was not acceptable by Biswajit Mahanty. In 2014, an FIR was registered by the University against Biswajit Mahanty. It alleged that he had entered the campus with five companions and had abused as well as misbehaved with the faculty and students of the ITM Department.

If you don’t refrain from coming to the ITM department, I will assault you by entering your home.

Police Complaint quoting Biswajit Mahanty

In 2015, the District Court gave its judgement on the arbitration petition filed by Star Computer Institute Pvt. Ltd. opposing the University’s refusal to renew the MOU. Unfortunately for Biswajit, the judgement upheld Ravenshaw’s right to terminate the MOU. Until 2015, cases pertaining to Ravenshaw were heard by single benches like Justice S.C. Parija, Justice Biswanath Rath, Justice B.R. Sarangi, Justice Sanju Panda, Justice A.K. Nath and Justice B.R. Nath. Most of these judgments were in favour of the University. Then came the alleged vengeance for upsetting Justice Indrajit Mahanty’s brother.

Judges are expected to recuse themselves from hearing cases where their kith and kin’s interests are involved, but Justice Indrajit Mahanty overrides such niceties without batting an eyelid.

Source: http://wakeupindia-designer.blogspot.com/2016/09/3-of-1060-print-all-in-new-window-judge.html

On December 9th, 2015, their case landed in front of the division bench comprising Justice D.P. Choudhury and Justice Indrajit Mahanty. Dominated by Justice Mahanty, they quashed the desperately needed recruitment, overturned the judgements from 2014 and slammed Ravenshaw in “all ways possible”. Surprisingly, this was not the end of their dismay. Justice Mahanty went on to take two suo moto civil proceedings against Ravenshaw and by March 2016, Justice Mahanty had passed eight judgments against them. It is astounding how Justice Mahanty allegedly went after Ravenshaw even though he had himself studied there. All the Ravenshaw related cases were eventually taken away from him in July 2018 following a petition filed by activist Chittaranjan Mohanty on behalf of the 8000 students of the University.

Clash over OJEE

Apart from burying Ravenshaw in legal bills and losses, these judgments have crafted a certain idea of Justice Mahanty: his brother is very dear to him, so much so that their biases are transferable. This was further reinforced by Justice Mahanty’s stand on OJEE (Orissa JEE).

Justice I. Mahanty’s many interim orders are in alignment with the commercial and political interests of his brother.

Source: http://wakeupindia-designer.blogspot.com/2016/09/3-of-1060-print-all-in-new-window-judge.html

Being the head of the Orissa Technical College Association (OTCA), Biswajit Mahanty’s concerns naturally revolve around students’ rights and filling more seats in colleges. On the other hand, journalist and RTI activist, Krishnaraj Rao opined that “more filled-up seats means fatter profits for Biswajit Mohanty and his fellow ‘educationists’.” Nonetheless, reason is irrelevant. The fact remains that OTCA and OPECA have been pushing for OJEE, which is Orissa JEE, to be conducted for vacant seats after JEE counselling. In 2014, the Supreme Court put a stay on OJEE. Despite this, an Orissa High Court bench comprising Justice Mahanty and some junior judges ordered the same be conducted in the years 2014, 2015 and 2016.

Another interesting fact is that Justice Mahanty’s brother, Biswajit Mahanty, is not just a lobbyist but also a politician. Even though he is now (2021) a part of Biju Janata Dal (BJD), he was a BJP member in 2015. This information had not been introduced until now for a reason: the aforementioned discussion drives out the possibility of one thinking that Justice Mahanty favoured BJP or was affiliated with it. There are no instances of any affiliation. Rather, various articles claim that it is his brother he cares about. Be that as it may, Krishnaraj Rao claims that the party could sense Biswajit’s influence on Justice Mahanty’s judgments, making the former an important pawn. There has also been an instance where the BJP praised Biswajit Mahanty.

Recognizing the value of his demonstrated power to sway the high court, BJP lovingly embraced “Pugi Bhai” Biswajit Mahanty in 2015.

Source: http://wakeupindia-designer.blogspot.com/2016/09/3-of-1060-print-all-in-new-window-judge.html

The Triple C Hotel Controversy

Violating judge’s code of conduct

In 2006, the year in which Justice Mahanty was elevated, he acquired homestead land in Cuttack, Orissa. This land was set to be developed into the Triple C Hotel. He sought permission for its ‘commercial cum residential purposes’ from the Cuttack Development Authority (CDA), which was eventually granted on July 7th, 2007. The permit specifically gave “Approval of Building Plan for construction of a three storeyed commercial cum residential building in favour of Hon’ble Justice Sri Indarjit Mahanty”. Here, granting commercial rights to a judge is extremely worrisome. Even if one chooses to keep the other ‘wrongdoings’ aside, the existence of a side business is violative of a judge’s code of conduct in itself.

13. A Judge shall not engage directly or indirectly in trade or business either by himself or in association with any other person. (Publication of a legal treatise or any activity in the nature of a hobby shall not be construed as a trade or business). – Restatement of values of Judicial life (Point 13)

Surprisingly, allegations against Justice Mahanty pertaining to abuse of power are not related to him favouring his brother but are also linked with events which facilitate his own causes. This brings the discussion to the issue that led to the investigation: the string of events pertaining to the Triple C Hotel. This can be divided into three problematic parts: crossing the building storeys limit, giving a judgement that allowed female employment in dance-bars (considered a case of conflict of interest) and most importantly, having any side business at all.

Overstepping the permit

Moreover, on January 15th, 2009, Justice Mahanty submitted an application to the State Bank of India SMECCC, Cuttack, requesting for sanction of Working Capital Limit under Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs). On February 6th, 2009, State Bank of India sanctioned the Term Loan for the construction of his hotel. The approval of this loan translates to backing a High Court judge’s business, which is problematic in the same way as CDA’s permit. Justice Mahanty’s loan account statements prove that the loan is being paid off from his account. Further, what is more disconcerting is the fact that the limits prescribed by the permit granted by the Cuttack Development Authority were crossed. While the document only approved three storeys, five storeys were constructed.

A case of alleged conflict of interest

Additionally, Justice Mahanty did not recuse himself from a case despite ascertaining a ‘clear conflict of interest’. In 2015, the Excise Department of the Government of Odissa announced the closure of three bars in Cuttack for employing female dancers and singers in violation of the Bihar and Orissa Excise Act 1915, specifically Section 25 (2) and (3). The law prohibits employment of women in bars. This was challenged by a hotelier, Prasanna Kumar Panda and the case was heard by a bench comprising Justice Mahanty and Justice D.P. Choudhury. On December 3rd, 2015, they gave a judicial order which stated that women can be employed as musical performers in bars and liquor serving restaurants across the State. The Pioneer attempted to justify the judgment by saying- “He only went by the ruling of the Supreme Court citing protection of rights of young men and women to make a legitimate living within parameters of social civility”. Nonetheless, women were, in fact, hired in a dance bar in the Triple C Hotel as music performers, which apart from being in clear violation of the Bihar and Odissa Excise Act 1915, also made him ill-suited to judge this case.

The presence of a side business, crossing of the limit set by the Cuttack Development Authority permit and the case of alleged conflict of interest are the ‘affairs’ that backed RTI Activist Jayanta Das’ complaint which in turn triggered the in-house investigation in September 2016 against Justice Mahanty and Justice Sahoo. In June 2017, the inquiry hit a snag when Justice Dipak Misra’s name cropped up in the investigation. A letter stating that the committee does not have the power to investigate an apex court judge was sent to the then Chief Justice of India, J.S. Kehar, following which the inquiry was immediately paused.

Justice Mahanty and Justice Dipak Misra

While the report was never put up on public domain which makes ascertaining the exact connection tough, there is an event that closely links Justice Mahanty and Justice Misra. According to Jayanta Das, Justice Dipak Misra had misrepresented facts while trying to acquire a part of public land which was meant to be distributed among the poor in 1979, for the development of a fodder farm. In an application to the Odisha government, he declared that his family owned 10 acres of land although none of it was in his name, he allegedly concealed this information in a subsequent affidavit. This affidavit later became the basis for the allotment of two acres of public land to Justice Misra.

This discrepancy was first noticed in 1985 by the additional district magistrate of Cuttack, C. Nayak. He further ordered the cancellation of the allotment as Misra came from a wealthy family, which made him ineligible for the land grant. However, the order was only taken into consideration in 2012 following a petition filed (in 2009) by Chittaranjan Mahanty, the same person who petitioned the Chief Justice of India and the Orissa High Court, on behalf of the university’s students, highlighting Justice Mahanty’s conduct on Ravenshaw-related cases. The high court, while hearing the writ petition, ordered a CBI enquiry, which in 2013 confirmed the alleged irregularities in the land allotments.

The case, along with CBI findings, was listed before Justice Indrajit Mohanty. From the day of case assignment to the days of the inquiry in question, no progress has been made on the case.

The case, along with CBI findings, was listed before Justice Indrajit Mohanty. From the day of case assignment to the days of the inquiry in question, no progress has been made on the case.

Regardless of whatever the connection may be, the probe was put on hold in June 2017 and was resumed in February 2018. On July 15th, 2018, the committee submitted its report to the then Chief Justice of India. Interestingly, the judge that held the office on the date in question was none other than Justice Dipak Misra himself. The inquiry was concluded and closed in August 2018 and no public action had been taken against it.

Three months after the abrupt end of the inquiry, Justice Mahanty was transferred to the Bombay High Court. He took oath as the court’s judge on November 14rth, 2018 alongside Justice Akil Kureshi who was transferred from the Allahabad High Court. It is ironic how the journeys of the two judges transferring to the Bombay High Court on the same day are the polar opposites of each other. Click here to read Justice Kureshi’s journey.

Bombay High Court

Unlike Justice Mahanty’s whimsical ventures in the Orissa High Court, his judicial journey in Bombay High Court has been that of a regular judge.

Although he did not get an opportunity to engage with any landmark cases, his judgements on lesser important cases can be seen as rational. For instance, in 2019, a bench comprising Justice Mahanty and Justice Kotwal held that marriages between a Hindu and a non-Hindu, performed following Hindu rites, are legitimate. The issue came up when a Hindu woman and her Christian husband filed for annulment of their marriage in 2017. Amidst litigation, the woman modified her plea and requested special relief regarding the couple’s legal standing with relation to their marriage. In its ruling in September 2018, however, the Family Court, Mumbai, rejected the appeal and said that it could not “legalise an already illegal conduct of the parties” since they had been married following Hindu rituals. Once the appeal was accepted by the High Court, it became apparent that the Bench led by Justice Mahanty had different opinions than the Judge of the Family Court.

The parties had got married as per Hindu rites though one of the parties was not a Hindu, but for that, labelling their act as illegal is unwarranted.

Justice Indrajit Mahanty’s response to the Family Court’s judge’s reasoning

He further stated that the Specific Relief Act not only deals with civil rights but also with declaration of legal character. He held that the petition was maintainable and legal, and the parties had the right to approach the Family Court (who were instructed to see the petition afresh) with it.

Just as the case discussed above, most of the judgments given by Justice Mahanty in Bombay High Court have an undertone of rationality and sensibility. However, what is strange is the fact that even though he was one of the senior judges in this Court, he was mostly assigned civil cases, taxation matters and other regular matters which can easily handled by junior judges. The reason(s) for the same remain an unsolved and ignored mystery. Nonetheless, Justice Mahanty did not have to spend much time in this Court. On October 6th, 2019, less than a year after his appointment in the Bombay High Court, he was elevated to the position of the Chief Justice of the Rajasthan High Court.

Rajasthan High Court

God has given me this responsibility thus I am not here for the post but to serve people. Small improvements can ensure transparency for the people.

Justice Indrajit Mahanty

Justice Mahanty took oath as the Chief Justice of the Rajasthan High Court on October 6th, 2019, and with that, he stepped into a role that defined a new milestone in his judicial career. Being the master of the roster, Justice Mahanty transited from judging Maharshtra and Goa’s regular cases to Rajasthan’s crucial cases.

In May 2020, a bench comprising Justice Mahanty and Justice Ashok Gaur took suo moto cognizance of the COVID outbreak in Jaipur District Jail which infected 130 prisoners and the jail superintendent. With the intention of preventing such hazards, the bench ordered Coronavirus testing for all newly arrested individuals. Additionally, they laid out a standard operating procedure for jails which illustrated the execution of the order.

In September 2020, Justice S.P. Sharma gave an interim order which instructed private schools to collect 70% of the tuition fees. This was in view of the cost reductions owing to the transition from offline to online schooling. The order was challenged by over 200 schools. The opposition had two major arguments: the order failed to consider the costs borne by schools for giving salary to its faculty and those borne in the arrangement of online classes’ facilities. Nonetheless, the judgment was upheld by the court since it was seen as ‘unfair’ for parents to pay the full fees. This judgment was challenged and debated upon heavily until it returned to the court of Justice Mahanty, who, instead of reversing the judgment (as witnessed in the previous case involving Justice Mahanty and an educational institution), gave the green signal to the interim order.

In contrast to the cases assigned to him in the Bombay High Court – cases which only affected and were specific to the complainant/defendant, Justice Mahanty had successfully moved on to cases which held bearings over substantial sets of the population of Rajasthan. This, however, does not mean he did not judge cases that decided the fate of individuals. As one might guess, these cases mostly turned out to be high profile. For instance, the judgment of the division bench of Justice Mahanty and Justice Prakash Gupta marked the end of the complicated internal war of BJP’s Ashok Gehlot and Sachin Pilot.

Justice Mahanty’s first two years as a High Court Chief Justice seem to have gone without a hitch. In fact, in Rajasthan’s first online Lok Adalat organised by Rajasthan State Legal Services Authority (RSLSA) under the aegis of National Legal Services Authority, Justice Mahanty highlighted that the Rajasthan High Court had disposed of most of their cases during the pandemic. Nonetheless, the end of his journey in the Rajasthan High Court is just over the horizon. In September 2021, the collegium headed by the current Chief Justice of India, N.V. Ramana, recommended eight new High Court Chief Justices and transfers of five sitting High Court Chief Justices to different High Courts, one of whom was Justice Mahanty. He was recommended as the Chief Justice of Tripura High Court.

Justice Mahanty’s journey has been incalculable from the start. When it almost seemed certain that he could be reprimanded for his actions in Odisha, the in-house investigation gave him a clean chit. When it was anticipated that his course of action would problematically be the same in Bombay High Court as they were in Orissa’s, he did nothing but perform a judge’s duties rationally. When it seemed that the tides around him had settled, his transfer to the High Court with the smallest jurisdiction was recommended. This latest development has, indeed, made his judicial future all the more unpredictable.

Justice Mahanty’s story is a reflection of India’s Judiciary as a whole. As great a system as it is, there are many questions that highlight the failures in it. Why was Justice Mahanty assigned cases where there was a clear conflict of interest? How was he able to obtain a loan from SBI for commercial property development when it is in clear contradiction to the guidelines of his conduct? Why did the Cuttack Development authority approve his ventures and allow him to perform unauthorized construction? Why was the investigation against him not followed through? Why have these issues not hampered his judicial career? The answers are all sitting somewhere in sealed documents, away from the public’s prying eyes, fueling the imaginations of activists.

Research by: Anshu

Edited by: Eklavya Dahiya