“Do not worry if the pace of the journey may sometimes seem slow but definitely worry if the direction is wrong.”

– Akil Kureshi

Akil Kureshi spoke these words at a webinar hosted by LiveLaw on How To Extend Class Room Training Into Good Advocacy. Sending a message to all aspiring lawyers, he added, “You’re young, you’re enthusiastic, you’re idealistic, your whole life is ahead of you. Never compromise in your principles when you grow. Have the courage to uphold your convictions.” These words are an accurate expression of Justice Kureshi’s own journey as a judge. A story that is ridden with many highlights and controversies. A tale worthy of a full-length feature film. Unfortunately for us, Bollywood would rather milk the Jolly LLB franchise which depicts Judges as moronic or comical characters than highlight the true plight of our Judiciary’s challenges. We recommend that you watch this 2-minute clip from Justice Kureshi’s webinar and hear the gravity with which he cautions us. His message is pertinent to all of us.

Who is Akil Kureshi?

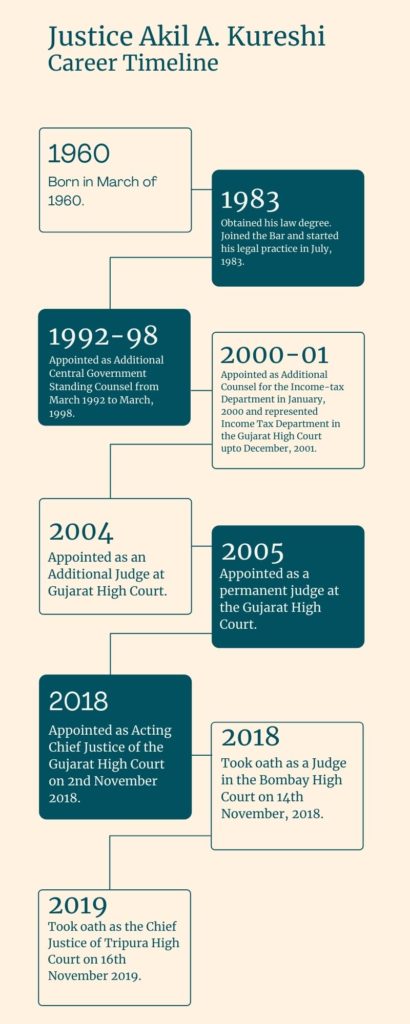

Justice Akil Abdulhamid Kureshi is the current (as of August 2021) Chief Justice of Tripura High Court. He began his journey in the legal field when he started his practice soon after joining the Bar in 1983. His educational qualifications include bachelor’s degrees in science followed by law. By 1992 – after 9 years of practice, Kureshi was appointed as Additional Standing Counsel for the Central Government where he dealt with the entire workload of the Central Administrative Tribunal at Ahmedabad. He handled a wide range of matters from land acquisition cases to criminal matters and even cases related to passports. He regularly appeared in private matters as well at the High Court of Gujarat. These too were diverse matters such as Special Civil Applications, Service and Non-service and Criminal matters. By the year 2000, Kureshi was appointed as an Additional Counsel for the Income-tax Department and represented it in the Gujarat High Court until 2001.

By the year 2004, Kureshi had been appointed as an Additional Judge at the High Court of Gujarat. This was a peculiar time for the state of Gujarat. On one hand, the Ambani brothers were fighting for control over the Reliance Empire following the death of Dhirubhai Ambani. On the other hand, the 2002 Godahara riots investigation had officially come to an end and charge sheets were submitted by the Gujarat Police. Rakesh Asthana (IPS) a special inspector general of police at that time was in charge of the investigation. As of August 2021, Rakesh Astana is the Commissioner of the Delhi Police which falls directly under the purview of India’s Ministry of Home Affairs – which is being led by Amit Shah. Amit Shah was also the Home Minister for Gujarat from 2002-2012. Justice Kureshi has a role in this entire saga and we will explore that part of history in a bit.

By 2005, Akil Kureshi was promoted from an Additional Judge to a Permanent Judge at the Gujarat High Court where he served for almost 15 years. For 8 days, Akil Kureshi served as the Acting Chief Justice of the Gujarat High Court. He was then transferred as a Judge to the Bombay High Court in 2018. A year later, he was appointed as Chief Justice of the Tripura High Court from where he is likely to retire in 2022. Analysing records from the websites of High Courts where he served, he has handed down more than 20,000 judgments throughout his career as a judge. No small feat. The former Chief Justice of Tripura High Court – Justice Deepak Gupta, while advocating for Kureshi’s elevation to the Supreme Court, described him as “one of the finest judges in the country”. He called him an honest man with competence and seniority on his side.

Former Tripura High Court Chief Justice Deepak Gupta, while advocating for his elevation to the Supreme Court, described him as “one of the finest judges in the country”.

Kureshi has rendered several progressive and influential judgments, thanks to his well-rounded experiences and his principled approach towards justice. He did not shy away from picking battles with giants. For instance, in 2014, the Gujarat High Court had asked the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) to form an independent committee to probe alleged violation of environmental norms by Adani Group for a project at Kandla Port Trust (KPT) in the state.

Justice Kureshi is well-known for his Gandhian background. He was born on March 7, 1960 in Gujarat. His grandfather Abdul Kadir Bawazeer was a close friend and lifelong associate of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi whom he accompanied from South Africa to India. Hamid Kureshi, Akil Kureshi’s father, was born in the Sabarmati Ashram and grew up playing in the lap of Gandhi. A renowned advocate, Hamid Kureshi remained the head of the Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust until his death in 2016. These links with the Gandhi family are sometimes speculated to be the reasons for his disputable transfers.

A Series of Controversial Transfers

On the 6th of August, 2010 while under investigation in the Sohrabuddin – Kausarbi murder case, a single-judge bench headed by Justice Akil Kureshi reversed the order of a Special CBI court and granted a two-day custodial remand of Amit Shah – the then serving Home Minister of Gujarat. Mr. Shah was then lodged at the Sabarmati Central jail for 2 days. Similarly, in 2012, a bench of Justice Akil Kureshi and Justice Sonia Gokani went head to head with the erstwhile Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi and upheld the appointment of Justice R.A. Mehta, a retired judge of Gujarat HC, as Lokayukta of the state. The government’s petition contested Gujarat Governor Kamla Beniwal’s decision, which was alleged to have been made without consulting the council of ministers. Kamla Beniwal has been a lifelong member of the Indian National Congress and harbored no special love for the BJP led government in Gujarat.

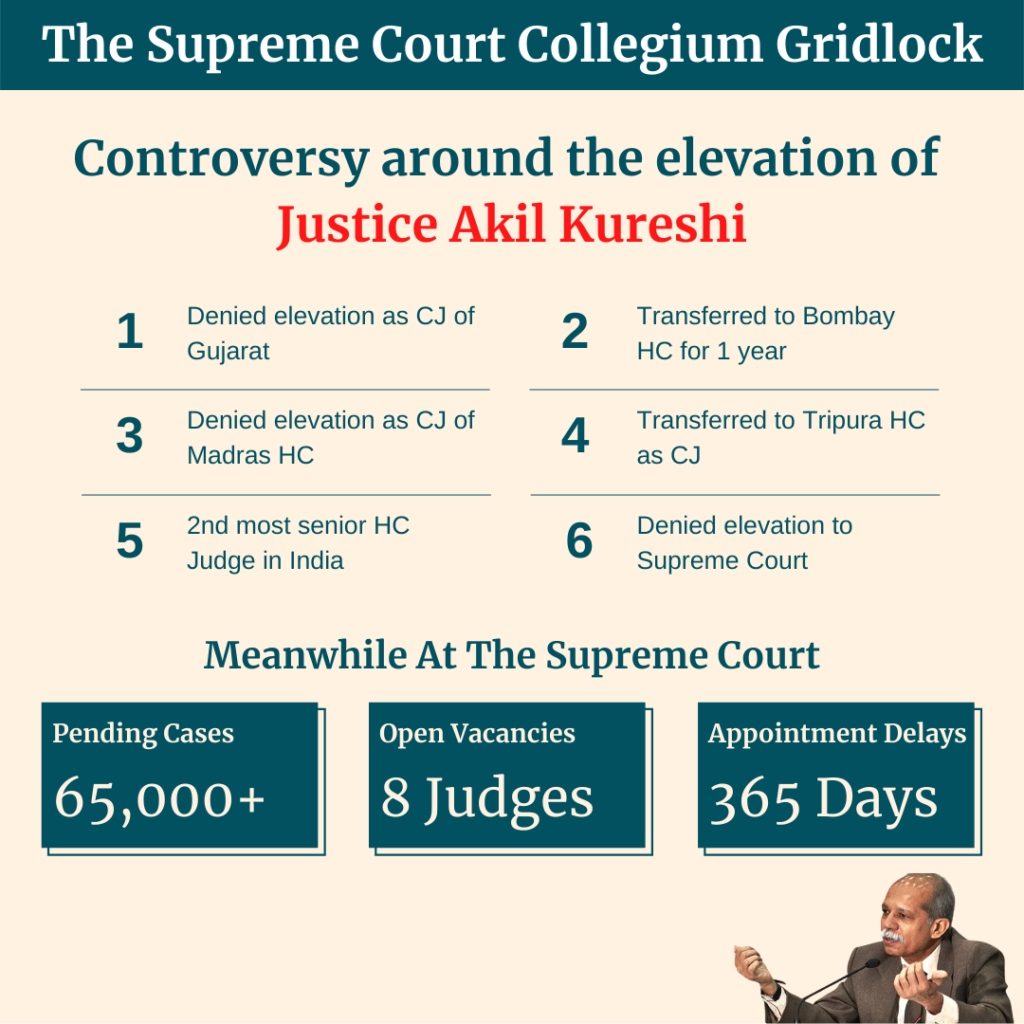

It is opined that these conflicts led to Akil Kureshi’s dislike by the Modi Government, which becomes apparent in the later phases of his judicial tenure. The controversial transfers started in 2018 when the Chief Justice of Gujarat High Court, R. Subhash Reddy was elevated to the Supreme Court. Justice Kureshi, being the second senior-most judge of the Gujarat High should have been appointed as the Acting Chief Justice. However, on October 29, just two days before Justice Reddy’s last day at the Gujarat High Court, the Supreme Court Collegium released a notification and recommended that Justice Kureshi be transferred to the Bombay High Court where he was supposed to take an oath on 14th November.

The reason given for this unprecedented decision – it was “in the interest of better administration of justice”. Subsequently, Justice Anantkumar S. Dave, the next senior-most judge after Kureshi, was appointed by the government as the Acting Chief Justice of Gujarat High Court. This was another problematic order as Justice Kureshi was supposed to fill the vacancy until his transfer to Bombay High Court. Ranjan Gogoi, the then Chief Justice of India objected to this decision compelling the government to issue a fresh notification allowing Justice Kureshi to serve as the Acting Chief Justice before his transfer.

“There can be little doubt left in the minds of those in the administration of justice that the transfer is punitive in nature.”

– Senior advocate Dushyant Dave

Needless to say that these contradictory decisions raised some clamour amongst the legal fraternity. The Gujarat High Court Advocates Association (GHCAA), led by senior advocate Yatin Oza, filed a petition challenging the transfer of Justice Kureshi to Bombay High Court. The bar found no merit in the rationale for his transfer and unanimously decided to protest against it. Their resolution mentioned that “such a transfer is unjustified and certainly has no connection with better administration of justice”. The petition also stated that Kureshi’s transfer “impinges on the independence of the judiciary“. Dushyant Dave, a senior advocate and former President of the Supreme Court Bar Association, wrote a column in Bar and Bench supporting the contentions raised by the GHCAA. He remarked – “There can be little doubt left in the minds of those in the administration of justice that the transfer is punitive in nature.”

Exiled from Home

After practicing for more than two decades and serving as a judge for almost 15 years in Gujarat High Court, Justice Kureshi was transferred to the Bombay High Court on 14th November 2018. Not more than a year after, another controversy arose when speculations about Centre’s dislike for Kureshi began to gain more traction.

On 10th May 2019, the Supreme Court Collegium recommended his elevation from Bombay High Court to become the Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court. The Central Government, a day before the results of the 2019 General Elections, released twelve notifications approving appointments of judges to several High Courts and the Supreme Court. However, these recommendations made no mention of Justice Kureshi. A month later, a notification issued by the Centre went against the Collegium’s recommendation and appointed Justice Ravi Shankar Jha as the Acting Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court. This provoked the Gujarat High Court Advocates Association (GHCAA) to file another petition in the Supreme Court, requesting a direction for the Centre to implement the Collegium’s recommendations. It was also stated that all of the Supreme Court Collegium’s recommendations had been followed except that of Justice Akil Kureshi.

After four months of unexplained silence, the Ministry of Law sent two letters to the Supreme Court in August of 2019 and requested the reconsideration of Kureshi’s elevation as a Chief Justice to some other court. While the contents of these letters were not disclosed, it was reported by The Print that Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad was of the opinion that Justice Kureshi was unfit to be appointed a Chief Justice. The letter reportedly contained arguments and materials against Kureshi’s judgements at the Gujarat High Court as reflecting communal bias.

The letter reportedly mentioned the Naroda Patiya massacre and Justice Kureshi’s recusal from the case. The case involved appeals against the August 2012 order of a lower court convicting 31 accused, including former BJP minister Maya Kodnani who was sentenced to 28 years in jail and Babu Bajrangi who was awarded a life term, for their alleged role in the massacre of 97 people during the 2002 riots. Kureshi recused himself from the case as his relative, advocate B.B. Naik decided to appear in the case which raised concerns over conflict of interest. However, he did express his regret and was reported saying that “it tarnishes the image of the institution and confidence of people”.

The Print also reported that their sources in the Supreme Court regarded these accusations as baseless. Due to some opposition from the Court, the Centre allowed Kureshi’s appointment to a smaller high court. On 20th September (the notification was dated 5th September), the Collegium led by Justice Ranjan Gogoi modified its recommendation to the Tripura High Court which was subsequently approved by the Government in another two months. This resulted in Kureshi’s transfer from Madhya Pradesh High Court to the comparatively smaller Tripura High Court, from where he is likely to retire in March 2022.

The collegium’s decision has been subjected to severe criticism on grounds of opaqueness and inconsistency in its rationale. Firstly, the notification mentioned that the modification was based on the letters and “accompanying material” provided by the Centre but failed to reveal the same. Secondly, there is no logical explanation as to why Justice Kureshi was appropriate for the position of Chief Justice at Tripura High Court but not at Madhya Pradesh High Court. If the Centre had displayed some reservations on the elevation of Justice Kureshi as a Chief Justice, and if he was indeed ‘unfit’ for the position then why was he elevated as the Chief Justice altogether? This also implies that the Supreme Court does not view different High Courts as being equally significant even though they perform the same constitutional role. The Bombay Bar Association had passed a resolution expressing their “strong disapproval” over the manner in which the notification was modified.

Nevertheless, the ambiguity surrounding Justice Kureshi’s judicial tenure does not end there. It goes on to become a part of the larger debate over the appointment of Supreme Court justices. In the last two years, it has been observed that the Collegium has reached a stalemate over the recommendation of names. There were no Supreme Court appointments in the year 2020. With the retirement of several judges approaching and the Collegium unable to reach an agreement, the situation becomes concerning, especially given the backlog of cases in the Apex Court.

Justice Kureshi’s elevation to the Supreme Court would give him 3 more years in the service as the retirement age for Supreme Court judges is 65 years. However, the disagreements over his name, along with the history of disputed transfers, make his selection seem unlikely.

Does Seniority of High Court Judges Even Matter?

One of the reasons for the lack of consensus in the Collegium includes the name of Justice Kureshi. He is currently ranked second in the all-India seniority list, following Karnataka High Court Chief Justice Abhay Oka, whose parent court is the Bombay High Court. While Oka will retire in May 2022, Kureshi will retire in March 2022. However, if one considers regional representation, the Supreme Court currently has three judges – Justices AM Khanwilkar, DY Chandrachud, and Bhushan Gavai from the Bombay High Court (Justice Oka’s parent High Court). On the other hand, Justice MR Shah is currently the only Supreme Court Judge from the Gujarat High Court (Justice Kureshi’s parent High Court).

Justice Kureshi’s elevation to the Supreme Court would give him 3 more years in the service as the retirement age for Supreme Court judges is 65 years. However, the disagreements over his name, along with the history of disputed transfers, make his selection seem unlikely. The deadlock in the Collegium is also causing a delay in the selection of other judges. Justice Markandey Katju, a former Supreme Court judge, expressed his disappointment on the ongoing conflicts through a Facebook post (which was later deleted but uploaded here). The post which was made in early 2021 revealed that one of the five judges of the collegium had said that he will oppose any recommendation of judges unless Justice Kureshi is recommended. The judge, in all probability, is Justice Rohinton Fali Nariman because the post had mentioned that the judge was going to retire this year. In the Collegium, only CJI Bobde and Nariman are set to retire in 2021 making the latter an obvious answer.

On 12th of August, 2021 Justice Nariman retired from the Supreme Court. Subsequently, on the 17th of August, 2021 the SC Collegium cleared the backlog of appointments which was held up due to Nariman’s stubbornness which arose from his support for Kureshi.

Justice Katju went on to criticise the Supreme Court’s decision to change Justice Kureshi’s transfer to Tripura High Court. An excerpt from the post:

“Justice Kureshi had been the senior-most Judge of the Gujarat High Court, from where he had been transferred to Bombay High Court, and he has an excellent reputation for his integrity and learning. … However, it seems that because he was a Muslim, and also because when he was a judge of Gujarat High Court he had passed adverse orders against the then Chief Minister of Gujarat Modi and then state cabinet minister Amit Shah (and for this reason had been transferred from Gujarat to Bombay), the Government strongly opposed his appointment as Chief Justice of a big High Court like the MP High Court. Evidently, the Supreme Court Collegium succumbed to this pressure, and to its shame recalled its earlier recommendation, and instead recommended his appointment as Chief Justice of Tripura High Court, which is a much smaller High Court, where he was then appointed.”

The Long History of Conflicts over Judicial Appointments

It is not the first time that disputes have arisen over the transfer of a judge. Kureshi’s transfers are a mere reflection of a long and chaotic history of judicial appointments which has been influenced by different governments, characters, issues, political ideologies, among others. Arghya Sengupta, founder and director of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, describes the narrative of judicial appointments as “Judges of diverse ideologies and upbringing, Law Ministers with varying degrees of inclination to interfere in the judicial process, Prime Ministers both non-interventionist as well as authoritative, controversies that have riven the nation, judicial decisions that have united it and continuing attempts at finding the ideal and hitherto elusive system of appointment which will secure the independence and high quality of the judiciary”.

As a matter of fact, appointments and the transfer of judges were one of the most debated topics in the Constituent Assembly. The Assembly wanted to institute a harmonious system where both the executive and the judiciary would work in tandem while making judicial appointments. The stress on executive involvement was based on the ideas of furthering transparency and public accountability. This was also because the system of executive-led appointments was commonly accepted by other major democracies at the time. For example; In the USA, appointments of the Supreme Court Justices are made by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

On the other hand, the adverse impacts of extreme executive interference in the matters of judiciary experienced during the colonial era were fresh in the mind of the drafters. An independent and competent judiciary was regarded to be of utmost importance by the Assembly. Nehru envisioned the judges of independent India to be of “the highest integrity” who could “stand up against the executive government, and whoever may come in their way”. Article 50 of the Indian Constitution mandates the state to take steps that separate the judiciary from the executive in the public services of the State. Provisions like fixed tenure, stringent impeachment process and deduction of salaries from the Consolidated Fund of India are some of the features in the Constitution to build an independent judiciary.

Discussing the dominance of executive and legislature over judicial appointments, Ambedkar described the process as both “cumbrous” and susceptible to “being influenced by political pressure and political considerations”. However, he had also expressed reservations against the binding opinion of the Chief Justice of India over judicial appointments. He cautioned, “it seems to me that those who advocate that proposition seem to rely implicitly both on the impartiality of the chief justice and the soundness of his judgement. I personally feel no doubt that the chief justice is a very eminent person. But after all the chief justice is a man with all the failings, all the sentiments and all the prejudices which we as common people have; and I think, to allow the chief justice practically a veto upon the appointment of judges is really to transfer the authority to the chief justice which we are not prepared to vest in the president or the government of the day.”

As a result, Articles 124 and 217 established a system where the President in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and other judges would appoint the Justices of the Supreme Court and High Courts respectively. The ‘consultation’ even though mandatory was not binding in nature. The Assembly intended to develop a system of appointments that were efficient, democratic and did not compromise upon the independence of the judiciary.

The Assembly wanted to institute a harmonious system where both the executive and the judiciary would work in tandem while making judicial appointments.

The Post-Independence Scenario

The initial years of independence saw a dominant position of the executive in determining judicial appointments. One of the earliest examples of executive interference can be seen during the Nehru government itself. In a letter to the then Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Nehru had expressed his hesitation in appointing Justice H.J. Kania as the first Chief Justice of India, the country’s highest judicial position. He felt that Kania’s attempt to stop the permanent appointment of Justice Basheer Ahmed to Madras High Court reeked of communalism. He agreed to drop the idea after an assurance from Patel who had cleared Ahmed’s appointment. After Kania’s death, the next senior-most judge was Patanjali Shastri. However, the position was offered to M.C. Setalvad, the then-attorney general. Setalvad was above 65 years, thus, could not accept the post. He suggested the name of M.C. Chagla but it was dropped after the demands from the judges of the Supreme Court to follow the convention of seniority.

The worst consequences of executive overreach were witnessed during the government of Indira Gandhi. The period is marked by an exponential increase in the political influence over the judiciary. In 1973, after the ruling in Kesavananda Bharti, the government elevated Justice Ajit Nath Ray (who gave a dissenting opinion) as the next Chief Justice of India over the three senior-most judges (J. M. Shelat, A.N Grover and K. S. Hegde) who had supported the Basic Structure Doctrine. Ray went on to uphold the government’s decision to suspend all Fundamental Rights including the right to life during the Emergency. After Ray’s retirement, the government superseded Hans Raj Khanna, who was next in line according to seniority but had given a dissenting opinion against the suspension of Fundamental Rights in the Emergency case. A number of similar instances followed during and after the Emergency period where democratic tenets of the Constitution were blatantly disregarded.

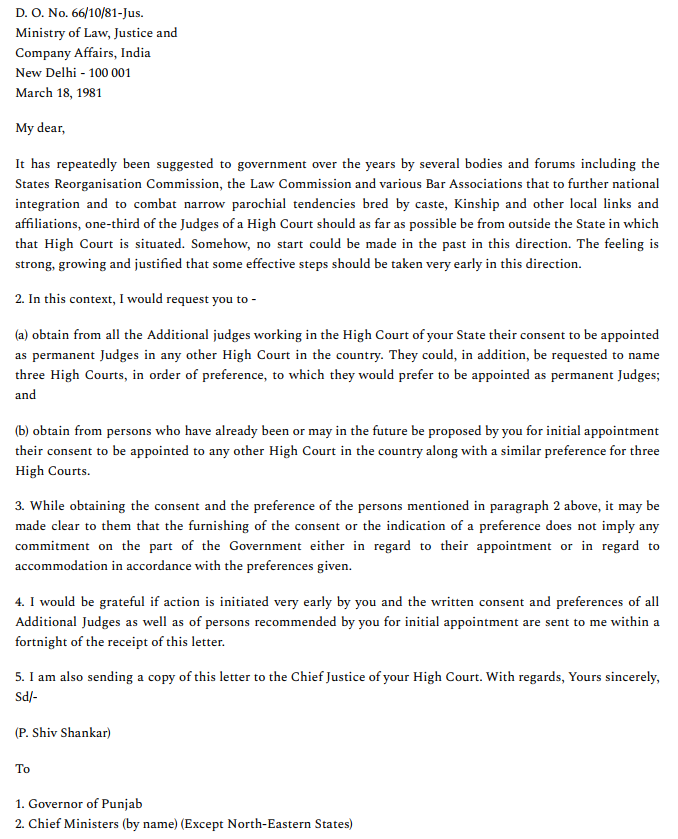

There were several attempts to control the judiciary by reducing tenures and increasing transfers of judges. P Shiv Shankar, the then Law Minister, had issued circulars to the chief ministers of different states to have one-third of judges in each High Court from outside the state on the grounds of promoting kinship and local affiliations. The circular asked for consent from additional judges to be appointed as permanent Judges in any other High Court in the country. This would have legitimised and increased the transfer of judges. The validity of the circular was ultimately challenged in the case of S. P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 (First Judges Case). There was also a proposition to include the political philosophy of judges as a criterion in the appointment process which was defended by S. Mohan Kumaramangalam, the Minister of Steel and Mines. He believed that it was a necessity to assess a judge’s view on “broad matters of the State” and “on the crucial socio-economic matters”.

However, it was feared that such a provision was only a medium to build a judiciary that would be subordinate to the needs of the government. Nana Palkhivala described it as a “made to measure” judiciary. Similar conflicts gave rise to an opinion among the public that only the judiciary was best placed to decide on its own composition. The legal fraternity felt that their present system failed to secure the independence of the judiciary. Y. V. Chandrachud, the CJI from 1978 to 1985, had called the appointment procedure “outmoded” which was “not purely based on merit”. After his retirement, he was reported saying, “Mrs. Gandhi never overruled me, but the government has got every weapon in its hands, so the vacancies are kept unfilled. The government tries artful persuasion, drops hints, and keeps egging you. No one is interested in having a good judiciary. No one is interested in having good judges”.

The worst consequences of executive overreach were witnessed during the government of Indira Gandhi.

The Birth of the Collegium

A number of petitions challenging transfers of judges and the validity of the circular issued by the law minister were filed under S. P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 (First Judges Case). The ruling of the case sided with the literal interpretation of the Constitution which highlighted the importance of the opinion of the Chief Justice but did not make it binding. The Supreme Court emphasised that the expression consultation used in Article 124 does not imply concurrence. Nonetheless, consultation with the Chief Justice should be real and effective. However, this interpretation provided the executive with legitimate supremacy over the procedure of judicial appointments. It was perceived that judicial independence was not adequately secured after the judgement in the First Judges Case. More instances of executive overreach changed the position of the Supreme Court which led to the case of Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v Union of India, 1993 or the Second Judges Case.

The Second Judges Case gave birth to the collegium system that we know and hear of today. It altered the ruling in the First Judges Case and shifted the power over judicial appointments to the Judiciary. The judgement remarked, “Should the executive have an equal role and be in divergence of many a proposal, germs of indiscipline would grow in the judiciary”. Accordingly, the Collegium consisting of the Chief Justice of India along with the senior-most judges of the Supreme Court was made responsible for the appointment and transfer of judges. The details about the functioning of the Collegium were further clarified in Special Reference No. 1 of 1998 also known as the Third Judges Case. In simple terms, the Collegium decides upon the names of the judges for selection to the High Courts and the Supreme Court. These recommendations are sent to the government for approval which has the authority to conduct an inquiry through the Intelligence Bureau (IB). The government can raise objections or ask for reconsideration, however, the final decision of the Collegium is binding on the government.

While the Collegium system still continues to be the present mode of the selection process, the procedure is mired by a number of flaws. One of the most ardent criticisms of the Collegium is its lack of transparency. There is hardly any information available in the public domain in relation to the functioning of the Collegium. Moreover, such opaqueness opens the door to other criticisms such as corruption and nepotism found among judges. Another major issue is the under-representation of women and people from scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Alok Prasanna Kumar, an advocate and a senior-resident fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, writes that the Collegium prefers practicing lawyers over promotion of judges from the subordinate courts which provide better diversity among the candidates. He describes the composition of high courts as an “ “old boys’ club” featuring largely male, upper-caste, former practicing lawyers”. This further reduces diversity among the candidates for selection to the Supreme Court. “Needless to say, the same judges will also find themselves within the topmost ranks of seniority in the Supreme Court, who then decide future appointments to the high courts, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of privilege”, he added.

In 2019, the Supreme Court while accepting that the office of CJI comes under RTI had held that only the names of the judges recommended and not the reasons for an appointment can be disclosed by the Collegium as it may impinge upon the independence of the judiciary. (Central Public Information Officer, Supreme Court of India v. Subhash Chandra Agarwal) This lack of information with respect to the criteria considered by the Collegium for the appointment of judges has been heavily criticised. There are no measures to investigate whether a judge selected may have a conflict of interest. Over the years, there have been allegations of conflict of interest among the members of the Collegium and the judges selected by them to the High Courts and the Supreme Court. In a report by the Caravan, a former Collegium member mentioned that there are no official meetings of the Collegium. The member added on to say that the usual procedure involves the CJI having “one on one discussions” with the members and that the judgements written by the prospective candidates are not even scrutinised. Justice AK Sikri, who was part of the Collegium from 2018 till his retirement in 2019, also addressed the issue in a panel session where he mentioned that the Collegium selects the candidates based on their “impression” which sometimes is sometimes the best result in the omission of deserving judges.

“Proceedings of the collegium were absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to public and history, barring occasional leaks”.- Justice Jasti Chelameswar

In Comes the NJAC

Justice Jasti Chelameswar, who was the only dissenter in a majority decision that quashed the establishment of NJAC (National Judicial Appointments Commission), wrote in his judgement, “Transparency is a vital factor in constitutional governance…Transparency is an aspect of rationality. The need for transparency is more in the case of appointment process. Proceedings of the collegium were absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to public and history, barring occasional leaks”. Chelameswar had cited two examples in his judgement to buttress his stance against the opaqueness of Collegium. In the first case (Shanti Bhushan & Another v. Union of India & Another, 2009), the elevation of a judge to Madras High Court was blocked by the Chief Justice due to political influence. He described the event as a “subversion of the law” by “both the executive and the judiciary”. The second example (P.D. Dinakaran v. Judges Inquiry Committee & Others, 2011) dealt with a problematic recommendation made to the Supreme Court by the Collegium involving P. D. Dinakaran, the then Chief Justice of Karnataka High Court. While his name was under consideration, several allegations of corruption were raised against him. Even though the elevation was halted, the recommendation “exposed the shallowness” of the collegium system.

The National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC), proposed by the National Democratic Alliance in 2014, was pushed forward as an idea to democratise the appointment and transfer process by reintroducing the involvement of the executive. With a total of six members, the Commission was to be headed by the Chief Justice of India. The other members included two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Law Minister and two “eminent persons” who would be selected by a committee involving the Chief Justice, the Prime Minister and the Leader of Opposition. One of these persons should either belong to a minority community, Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), other backward communities (OBC) or should be a woman. The NJAC bill was passed by the Parliament as the ninety-ninth Constitutional amendment. The Supreme Court bench comprising JS Khehar, J. Chelameswar, Madan B. Lokur, Kurian Joseph, Adarsh Kumar Goel ruled the bill as unconstitutional under Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association vs Union of India (Writ Petition (Civil) no. 13 of 2015) with a 4:1 majority where Justice Chelameswar was the lone dissenter.

While many had welcomed the idea of NJAC as a means to promote transparency, wide concerns were also raised with the implications of such a Commission. The legal fraternity, as a result, was highly divided when the NJAC Bills were released. One of the major arguments in favour of NJAC was that it furthered the principles of the Constitution which had envisioned a system where both the executive and the judiciary would have a role in the appointment process. Moreover, NJAC was proposed to be a more democratic and inclusive body that would have improved judicial accountability in matters of appointment. On the other hand, the concerns raised were more associated with the NJAC bills. The major concern was that the NJAC did not solve the menace of opaqueness existing with the current Collegium system. Thus, the practice of nepotism, corruption, trade-offs and favouritism could have easily been carried on under the umbrella of NJAC. Secondly, the NJAC amendment had added Articles 124 A, B and C in the Constitution to replace the Collegium. Article 124 C gave the Parliament critical powers to govern the functioning of the NJAC. This brought back the memories of the past where the dominance of the executive had resulted in gross violation of the independence of the judiciary. The fact that the Bills were passed in a haste overshadowing the procedure of long debates and discussions only validated these suspicions.

The Supreme Court, while ruling NJAC as unconstitutional, did address the need for a more transparent and accountable procedure of appointments. It asked the government to formulate a new Memorandum of Procedure (MOP) of appointing judges in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and also listed a few suggestions to improve the working of the Collegium. The current MOP was set up in 1999. However, there has been a constant deadlock on certain issues after several correspondences between the two authorities over the past five years. One of the issues pertains to the rejection of a candidate on the grounds of “national security and overriding public interest”. In a letter from the law ministry to the Supreme Court in 2017, the government had asked to keep the reasons for such rejection confidential and shared only with the CJI. As reported by Hindustan Times, that was the last communication between the two sides. The letter also mentioned two other issues of contention between the two. The Supreme Court did not approve of the government’s demands of creating a secretariat for clearing names of judges or forming a committee of judges who were not a part of the Collegium to screen complaints against sitting judges. There was also a demand for having search and evaluation committees for selecting candidates which were opposed by the Court.

In October 2017, Justices AK Goel and U. U. Lalit, while hearing a petition, highlighted that the issue of MOP should not stretch for an indefinite period even though the Supreme Court had not fixed a time limit. Subsequently, the matter was placed before another bench led by the then CJI Dipak Mishra who recalled the previous order given by Judges Goel and Lalit, saying that the matter should not be handled on the judicial side. Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde has suggested the Supreme Court release the entire correspondence on MOP between the government and CJI in the public domain to take appropriate actions. There have not been any major developments in the situation for a while.

Thus, with no major initiatives in sight, the uncomfortable silence over the disputes lingers on. Meanwhile, the Executive finds other illegitimate ways to influence the judicial decisions taken by the collegium behind closed doors.

The Judiciary’s Independence is a Myth

Regarded as a man of integrity, Justice Akil Kureshi has one of the highest judgement delivery rates in the country. It is estimated that he has given more than 20,000 judgements at the Gujarat High Court. Justice Ravi Shankar Jha, who was selected in his place as the Chief Justice of Madras High Court, has pronounced only around 2500 judgements throughout his judicial career. More than often, Kureshi has given orders that may have irked the ruling governments. In 2012, the Gujarat High Court had issued a contempt notice to the State Government for not complying with its order regarding compensation to victims of the 2002 riots whose shops were destroyed. During the 2017 Gujarat Assembly elections, the Gujarat High Court had issued notice to the Election Commission and the central government on a petition moved by Congress’s state unit seeking that EVMs and VVPATs that were found defective be sealed and not used in the succeeding Assembly polls.

“Justice Akil Kureshi apart from his manifest prejudice against BJP is gifted with exemplary shallow knowledge of law, and in charging Sh. Amit Shah of frivolous offences with all respect to Justice Kureshi even an entry-level judicial officer would have desisted of exhibiting such extravagant

amateurishness.”

In 2019, a complaint was filed by Advocate Vijay S. Kurle (State President of Maharashtra and Goa of the Indian Bar Association) against justices Akil Kureshi and Sharukh Kathawala. The complaint contained remarks and accusations raised against Justice Kureshi which were: i) Of having a bias against the Bharatiya Janata Party for having charged Amit Shah with “frivolous offences”, ii) Attempting to influence the Collegium through Advocate Yatin Oza who had filed writ petitions against his transfers. It also questions the orders of Justice Kureshi in two contempt petitions. However, a close reading of the letter shows little proof backing such accusations, raising doubts on the credibility of the complaint altogether. The frequent usage of politicised or harsh words such as “incompetent”, “psychopath”, and “Tukde Tukde Gang” in an official complaint suggests that its author might have strong passionate desires for revenge.

A copy of the complaint filed by Vijay Kurle

The complaint also defamed Senior Advocate Fali Nariman, who had advocated the cause of Kureshi, calling him “the cynosure of Lutyens media and the Khan Market brigade…known for his exemplary crusade in defending the anti-nationals and seditionists”. It is pertinent to note that advocates Vijay Kurle (author of the complaint), Nilesh Ojha and Rashid Khan Pathan have also made scandalous allegations against the Supreme Court judges RF Nariman and Vineet Saran. They were charged with contempt proceedings by the Supreme Court (bench of Justices Deepak Gupta and Aniruddha Bose) for the same and were punished with simple imprisonment for a period of 3 months each along with a fine of Rs. 2000.

On the contrary, Kureshi also received widespread support from the legal fraternity especially the Gujarat Advocate Association during this period of controversies. He has been lauded for his judgements and legal acumen by a multitude of lawyers, judges, and law students throughout the years. Advocate Krishnakant Vakharia recollects, “Even as a lawyer, soft spoken Justice Kureshi’ s integrity was above board. He is a rock solid judicial person. It has never mattered to him who a person is, whether you are the junior-most or the senior-most. He is a judge of meticulous credentials, unimpeachable integrity and unassailable grace”. Senior Advocate Dushyant Dave writes about Justice Kureshi as “a judge with impeccable character, integrity, sincerity, courage and efficiency. He combines these characteristics with deep acumen in law. He is fiercely independent from all considerations, political or economic. He writes outstanding judgments which are not only interesting to read, but are difficult to assail before the Higher Court”.

The unprecedented changes and constant delays in the transfers of Justice Akil Kureshi highlight the pernicious impact of an ailing system. Whether the problem is simply internal politics or whether it is something else, the system does not reward those who uphold its integrity the most. Connecting the facts of the case reveals that Kureshi had given certain judgements that went against the interests of Modi and Shah during their tenure in Gujarat as Chief Minister and Home Minister respectively. Later on, his elevation as the Chief Justice to Gujarat and Madras High Court were disapproved for reasons not disclosed to the public (since the contents of the letter sent by the Law Ministry to the Collegium were not officially released). On the other hand, the collegium has also failed to divulge any information on the basis of which it decided to change its recommendation. This is but an example of executive overreach in judicial appointments.

As a result, the sole objective of the collegium, which was to shield the judiciary from political sway, stands defeated. Executive interference in the matters of the judiciary is as prevalent as necessary for those who hold power.

Research By: Kashish Siddiqui Khan, Aastha, Rohit Mehta

Edited By: Eklavya Dahiya